Lies in the Levant

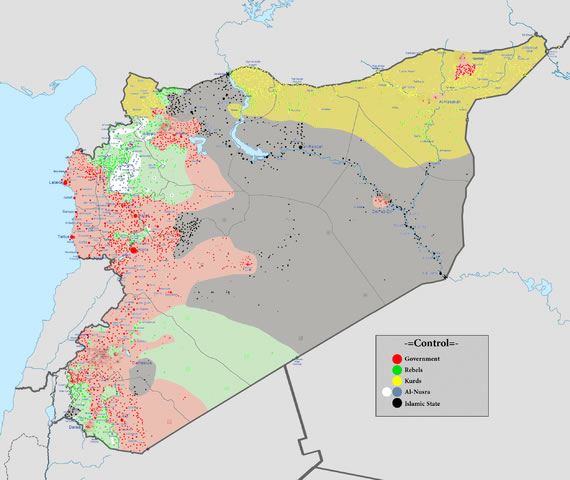

photo by By Wikipedia user “NordNordWest”

A glimpse at the various factions at war in Syria.

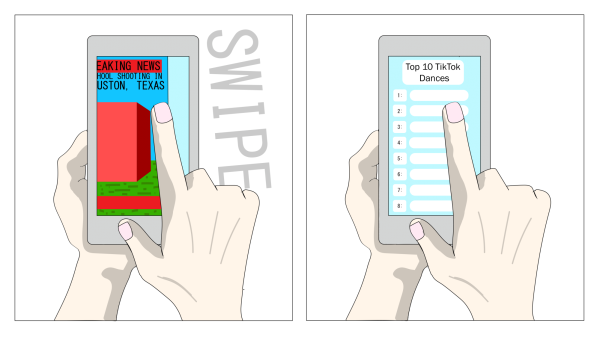

The line between entertainment and objective news has become harder and harder to define in the modern era. Teasers for political debates are intensified with Sunday Night Football style music and announcers in the background; rude, rambunctious, reality show type behavior yields higher ratings in both news and politics. Worst of all, complex conflicts like U.S.-Middle East intervention against ISIS have become greatly simplified in the hands of major news networks and social media.

ISIS, a self-proclaimed Islamic caliphate or empire with a name translating to “Islamic State in Syria/Levant,” has gained a massive swathe of land in Iraq (and subsequently lost a large amount of it). Their rise occurred in the wake of the U.S-led war against the late dictator of Iraq Saddam Hussein, who heavily policed the state, and in a way, prevented Islamic extremism from catching on. The terror group thrives on the oppression of minorities while broadcasting their brutal acts to incite fear or, for their supporters, inspire loyalty.

Meanwhile, many political pundits have called for either increased aggression against the group or direct confrontation with ground troops – but in doing so, they not only overlook the precarious state of both Syria and Iraq, but marginalize the locals in pursuit of a problem already beginning to wane as the group has done a poor job at sustaining themselves. Such actions would amount to nothing more than a waste of U.S. troops and even a possible proxy war between tense Western powers like Russia and the American States. It must be understood that while ISIS represents a despicable interpretation of a brotherly religion, strengthening U.S. intervention will have far too detrimental effect on the region.

Based on ISIS’s activity in Syria and Iraq, it can be concluded that the loosely organized group can only flourish in regions of instability. Syria is currently embroiled in a bloody civil war while Iraq, Syria’s neighbor, has spent the last decade ravaged by the rise of terrorist factions. No attempts at expansion past these two countries have been made, nor could they reasonably as the army of ISIS has failed in the face of well-grounded foes like Assad’s regime and the primarily Kurdish forces of the People’s Protection Units.

Consequently, the only serious threat the group poses is that of terrorism – but ground troops against the actual army would not be a preventive measure against bombings and mass shootings. The group is primarily ideological and thus has no proper rank, command or authority in spite of the fact that an obscure “caliph” occasionally speaks out. Therefore, any extremist could plausibly commit an act of violence while professing allegiance to ISIS and be accepted by the group hell-bent on terror over the establishment of a nation. Long after ISIS ceases activity, lone wolf extremists will continue to act until authorities manage to balance paranoia with objective diligence in national security. Lashing out on the weakened region in the hopes of eradicating the belief will prove as futile as all wars on abstract concepts have in the past, whether it is the War on Terror or the War on Drugs.

If the U.S. war in Iraq has taught the West anything, it should be that attempting to define a clear foe in the midst of a complicated civil affair is always catastrophic. After deposing Hussein during the Iraq war, a vast array of enemies sprung from the remnants of his regime and proved too numerous for the American-backed forces, even culminating in a 2006 civil war. The massive amount of losses in U.S-led forces resulted in many considering the war a Pyrrhic victory for America.

The primary conflict did not stem from the initial war – it was the subsequent emergence of opposing factions that made it hard to focus solely on maintaining peace. In Syria alone, the land is engulfed in a well-publicized civil war, but the majority of media coverage is about ISIS, Syrian/Kurdish rebels, and Assad’s regime. In reality, an equal, if not greater, number of groups than in Iraq during the war are warring with one another in the region. Sunni Islam forces include ISIS and the rebel’s allies of the Gulf States, while Shi’ite Islam adherents comprise the Iranian forces, Lebanese group Hezbollah and Assad’s government. If that summary was confusing, then imagine the headache one would get after taking into account how many Iraqi factions engaged the U.S. coalition. Fractured regions mean casualties for civilians, invaders and local rebels alike. Of these many factions, the one who reigns triumphant will be the one the population, not the U.S. or any other Western country, will have to deal with.

Outright support of any of the lesser-known factions could have repercussions akin to that of when the U.S. supported Osama Bin-Laden’s Afghan resistance against the Soviets in 1979. Historically, the Afghan forces went on to comprise the universally detested Taliban and Ahmad Massoud’s Northern Alliance. The moderate Alliance would fall to the Taliban, and a wave of terror would flood the country.

While Kurdish forces are commonly viewed as the best option for winning, it is a widely-known fact that the group, oppressed for the past century, has long yearned for autonomy and committed terrorist acts against Turkey in attempts to gain it, leading to worries that a victory for them could result in Turkish tension. The rebels, much like all revolutionaries, promise reform but still do little to help their own people in pursuit of their goal. ISIS and Assad are obviously no better, and too frequent bombings or ground troops that result in the unintentional deaths of any of those forces undermine the message of freedom the U.S. tries to convey. It may be a grim reality, but just as with the American civil war, it seems the only viable path to freedom lies in letting the groups battle until one prevails. The victor, however unethical they may be, will be the one to maintain the country, and if the people truly oppose this rule, they will once more take up arms and rebel with even more ferocity than before.

Ultimately, dictating the future of a country based on one’s own ideologies is no different than colonialism, where Western powers imposed their notions of “revolution” on the locals. The most the U.S. can offer to Syria without influencing the country too severely is the same amount of bombings with sufficient resources to the natives for combatting ISIS. For the residents of Syria and Iraq, this is more than an oversimplified problem for the foreign media to pity and profit from. This is an issue that, contrary to what the opponents of President Obama and some outspoken students may say, cannot be solved by simply bombing one faction and letting another thrive. In the final push against Islamic extremists and oppressive governments, only the local majority will be able to decide who deserves to triumph and by what means they will do so.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Hagerty High School. We are an ad-free publication, and your contribution helps us publish six issues of the BluePrint and cover our annual website hosting costs. Thank you so much!