Your donation will support the student journalists of Hagerty High School. We are an ad-free publication, and your contribution helps us publish six issues of the BluePrint and cover our annual website hosting costs. Thank you so much!

Girl Code

Science, technology, math and engineering. For some, it is the bane of their existence. They wake up each morning dreading physics worksheets and calculus quizzes. For others, it drives their academic careers. Between science fair ribbons, neatly written chemistry flashcards and Mu Alpha Theta competition trophies, the trials and tribulations of STEM push them to forge forward into college and beyond with dreams to pursue computer science, astrophysics, bio-chemical engineering and mathematical neuroscience.

Science, technology, math and engineering. For some, it is the bane of their existence. They wake up each morning dreading physics worksheets and calculus quizzes. For others, it drives their academic careers. Between science fair ribbons, neatly written chemistry flashcards and Mu Alpha Theta competition trophies, the trials and tribulations of STEM push them to forge forward into college and beyond with dreams to pursue computer science, astrophysics, bio-chemical engineering and mathematical neuroscience.

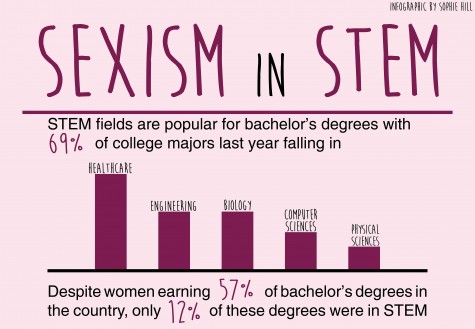

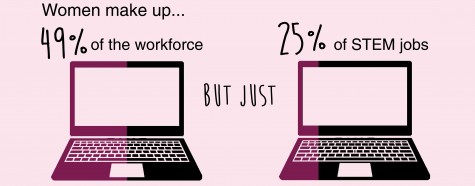

Like any competitive collection of college majors and career opportunities, STEM-based fields pose their respective difficulties. Unlike the academic records required to be a clinical psychologist, an English teacher or a museum curator, STEM fields can come with a series of obstacles originating from an idea many believe has diminished over the years: sexism.

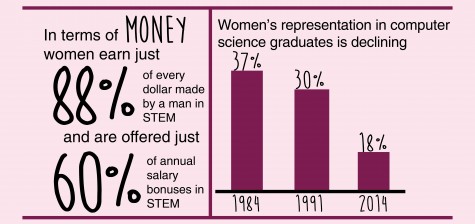

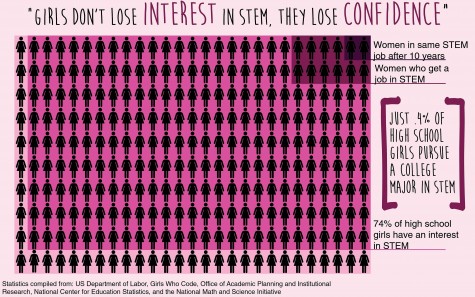

Since 1984, women with jobs in STEM has decreased from 34 percent to just 18 percent in 2014. This comes as a surprise considering the fact that hundreds of thousands of job positions will open over the next few years and America’s job market is in need of STEM workers. The U.S. Department of Labor projects that by 2020, there will be 1.4 million computer specialist job openings. However, American colleges are only expected to produce enough qualified graduates for 29 percent of these jobs.

The recent push to fill these openings includes encouraging girls to pursue STEM and has been seen in Girls Who Code and other programs established to produce the workers needed to maintain the job market.

Initial interest is not the problem, since nearly 74 percent of high school girls show an interest in STEM. In contrast, only .4 percent go on to pursue a STEM major in college. These programs aim to end the adversity girls face from a young age by inspiring girls to program, calculate and build their futures.

GIRL CODE ON CAMPUS

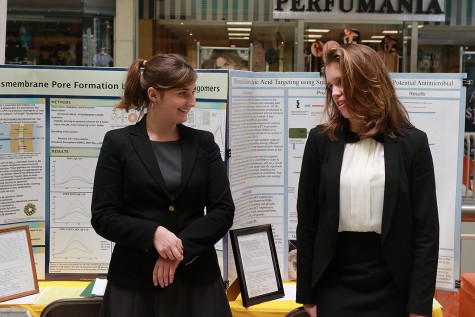

For juniors Madison Dishman and Victoria Guise, the disparity of female participation in STEM, specifically coding, caused them to create Girl Code.

The club was established to encourage girls to be exposed to computer science without the pressure of grades. After the discontinuation of the programming class last year, Dishman and Guise wanted a way to allow girls to try out an integral component of gaining technological prowess in a positive environment.

![“All careers in your future will require some technical understanding and modeling and simulation and Girl Code provide students with a safe place to learn and practice various skills related to building a career in [anything] you want to pursue,” modeling and simulation teacher Lindsey Spalding said. As the sponsor of Girl Code, she hopes to inspire students to integrate technology in any profession.](https://hhsblueprint.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Girl-Code-small-475x267.jpg)

“All careers in your future will require some technical understanding and modeling and simulation and Girl Code provide students with a safe place to learn and practice various skills related to building a career in [anything] you want to pursue,” modeling and simulation teacher Lindsey Spalding said. As the sponsor of Girl Code, she hopes to inspire students to integrate technology in any profession.

Both girls grew up in homes where they were constantly encouraged to pursue computer science. Dishman, whose father is a programmer, built up the idea that she could do anything she set her mind to. She says she wants to bring that positivity to other girls.

“We started Girl Code because [we] wanted to provide a safe learning environment for girls who don’t have parents that encourage them to pursue coding,” Dishman said. “We want them to know they aren’t limited.”

The sponsor for Girl Code, modeling and simulation teacher Lindsey Spalding, says the club is geared toward female beginners who have always had an interest in computers, but never really had a chance to try it out. She says even if they leave without coding proficiency, the exposure is great for college, resumes and jobs and does not carry the commitment of a typical class or the intimidation of facing a largely male club.

“We like integration, for sure, but because the competitive coding club is so male dominated, Girl Code offers a pressure-free way for girls to learn that it’s really not quite as scary as they think,” Spalding said.

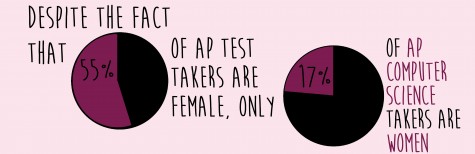

In high school, 55 percent of Advanced Placement test takers are female, but in AP Computer Science, just 17 percent are girls. Guise says that because girls are the minority in those types of classes, it can be harder for them to ask questions or speak up in class.

“If there  were more girls in the classes, they would be more confident,” Guise said.“People assume that girls can’t do ‘manly things’ like code or build things, so I’m hoping this club reminds girls that they can do anything that guys do.”

were more girls in the classes, they would be more confident,” Guise said.“People assume that girls can’t do ‘manly things’ like code or build things, so I’m hoping this club reminds girls that they can do anything that guys do.”

This pressure for girls to not follow STEM-based fields because it is a “man’s job” is felt on campus, even if it is less strong than in other parts of the country. However, the good fortune and financial stability of Hagerty that has led to a lesser sense of STEM gender discrimination does not extend evenly across classes and clubs. Senior Lucy Chen, president of the robotics club, says she’s aware of the assumption that boys are better than girls in STEM.

“We have this problem in our [robotics] club where some girls feel as if the guys are more experienced when really they only know about as much as [the girls] do,” Chen said. “The girls try not to seem too confident when providing input in case they are wrong.”

EARLY PRESSURE

This fear of failure is present in any class, but it seems to be especially poignant for girls in math and science subjects, says Chen.

Freshman Reagan Pomp presents her project to media specialist Po Dickinson. Pomp studied the differences in chemical and physical sunscreens by testing their efficiencies on pigskin. She is one of the six girls in the experimental science class, and says the support system of women in STEM has inspired her to continue pursuing science.

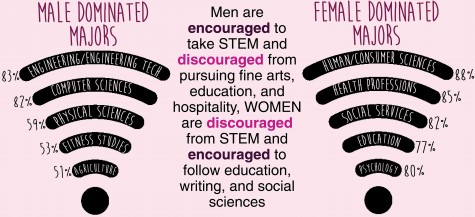

She also asserts that the expectations of gender roles in STEM in high school begin early. Growing up, she says boys are encouraged to play with STEM-related toys: Legos, model trains and robots. On the other hand, girls are typically encouraged to play with dolls and arts and crafts.

Even girls whose parents do not push gendered toys find themselves succumbing to the pressure to fit in with their friends by purchasing toys targeted for girls.

“It has been ingrained into our society that STEM fields are mainly for males and are male dominant,” Chen said. “It can be intimidating to challenge that idea.”

Others, however, believe that the sexist stereotypes that permeate STEM pursuits are in-part upheld by their targets. Dr. Romina Jannotti, a chemistry teacher who has her PhD in Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology, says that in order for girls to be better accepted into the STEM community, they need to not make STEM a choice.

“The basic sciences – biology, chemistry and physics – should be requirements and not options,” Jannotti said. “Encourage students to challenge themselves at every turn and to learn to be part of a diverse work force.”

Jannotti says that familial responsibilities also contribute to sexist stereotypes in STEM. Employers assume women will be engaged in raising children and taking care of the household, not forging the future in chemistry research or electrical engineering. While these gender roles are lessening their grip on the public, their change is slow.  Offhand comments are common for women in STEM. Expectations that girls need more help in math-based subjects and that girls are “squeamish” or “weak” are voiced in labs and during dissections. This type of attention extends itself as girls find themselves the subjects of dress code more often than their male counterparts.

Offhand comments are common for women in STEM. Expectations that girls need more help in math-based subjects and that girls are “squeamish” or “weak” are voiced in labs and during dissections. This type of attention extends itself as girls find themselves the subjects of dress code more often than their male counterparts.

“I had to endure comments about the length of my nails, or the length of my hair, or the height of my shoes,” Jannotti said.

She asserts that feminine characteristics are called out for their lack of lab safety, practicality or professionalism in lieu of addressing an underlying assumption that a woman does not belong in a class of mostly men.

FINDING A FOOTHOLD

Senior Claire Weaver and junior Tess Marvin are two of six girls in an eight person experimental science class on campus. Weaver and Marvin’s project, which studied the causes of Alzheimer’s in certain proteins, placed second at the state science fair. They are part of a concentration of STEM girls who defy gender assumptions.

Among these girls, some say they do not feel outright gender discrimination, but feel more pressure to win awards than their male counterparts. The assumption that boys do not need to validate their projects whereas girls need to prove their worth with awards, creates another obstacle girls face in STEM.

“I think that a lot of people judge success in science fair based on how a person places in the regional fair of if they go to the state competition or not,” junior Tess Marvin (pictured right) said. “For me, these are exciting indicators of hard work, but they are not the end all be all measure of success.” Marvin’s project researched possible causes of Alzheimer’s in certain proteins with partner senior Claire Weaver.

“How I placed didn’t change the work I did,” Marvin said. “I love knowing why and how the world ticks, so I was already excited about my project before I even went to the regional fair.”

Marvin’s excitement about STEM is common in her experimental science class. She says the encouragement of her teachers has helped to foster her fascination with the world around her, inspiring her and her classmates to tackle projects far more sophisticated than any baking soda and vinegar volcano.

Junior Samantha Bates, who shares a similar excitement in scientific curiosity, did a project on iron fertilization in aquatic systems and placed second in the regional science fair. Bates says experimental science teacher Sarah Evans is a huge inspiration for young girls interested in STEM. She describes the culture of unashamed curiosity and discovery Evans pushes for in her class as similar to what is found in Girl Code.

“I joined Girl Code because I was interested in coding and because the atmosphere is casual,” Bates said. “You get to hang out and try out new things with friends and food.”

The club is still small, with about five to 10 people showing up for meetings. The attendees work together to understand coding for all sorts of real-world applications including, but not limited to, finance, art, engineering, project management and web design. The club hopes to inspire girls with all sorts of interests to incorporate computer programming into their lives.

“Girl Code allows girls to practice leadership and learn new technical skills they may not have an opportunity to learn elsewhere,” Spalding, said.

Spalding says the original decision to sponsor the club came from the fact that the only other programming group on campus after the discontinuation of the programming class was the competitive coding club. She adds that the comfortable, student-run environment allows girls of all levels of interest to grab a computer and join in and start the technical integration she thinks is crucial to a well-balanced education.

“We want students to learn real world problem solving but we continue to teach isolated subject areas,” Spalding said. “We limit real world experience due to interruptions in standardized testing.”

“We want students to learn real world problem solving but we continue to teach isolated subject areas,” Spalding said. “We limit real world experience due to interruptions in standardized testing.”

Spalding says that like students can be distracted with awards, they are also disrupted by standardized testing, which is a detriment to both boys and girls. This sentiment is shared by members of her club and by the students in experimental science who say that the need to get awards and pass tests supersedes that of the importance of discovery and learning and that this attitude adversely affects girls more because they are then less likely to go out of their way to pursue STEM interests.

This means that until a different approach toward teaching is introduced, sexism-based disparities in STEM will continue to persevere.

Spalding also says that although she hopes to see a total reconfiguration of the school system to favor technical integration, she doesn’t see it happening anytime soon.

CHANGING THE GAME

“The girls in my class are doing amazing graduate level research. They are world’s beyond me, but I keep pushing them to do better,” experimental science and physics teacher Sarah Evans (pictured left) said. “I hope I encourage my students every day as a female in physics.” Of the eight students in the experimental science class, Lauren Neldner (pictured right) is one of six girls. Her project focused on bridge suspension during seismic activity.

On campus, the disparities of STEM abilities are not as obvious. Maybe it is because of the fact that the student demographics are typically homogeneous, or maybe it is due to the opportunities found in the modeling and simulation program and the rigorous AP STEM classes offered to students, but the gender gap in classes is much more even than the national average. Nevertheless, teachers like Spalding, Evans, who also teaches physics and calculus teacher Carolyn Guzman do their part to provide opportunities and encouragement to students for whatever they wish to pursue, regardless of gender.

“I see my female students comparing themselves to my male students. This attack on self-confidence is the number one reason why girls do not think they are good enough to pursue STEM careers,” Evans said. “I hope I encourage my students every day as a female in physics.”

With AP pass rates far exceeding that of the county averages, Evans, Guzman and Jannotti all seek to have classrooms where gender is as important as the color of a student’s shirt or the type of pen they use for lab reports.

“I think females are changing so that when faced with stereotypes, they use it for fuel to push themself to succeed,” Guzman said. “Females are starting to believe in their own intelligence and that they can accomplish anything with effort.”

Spalding believes that the best way to continue this trend is to challenge institutionalized prejudices in classrooms with more funding and more options.

“I think a major obstacle we have in promoting a higher technological education for both males and females is school infrastructure and teacher training,” Spalding said. “Schools should continue to promote equal education in all aspects, but until we offer a more interdisciplinary technical learning environment, I don’t see a big change in our near future.

Spalding says the need for men, women, boys and girls, to work together without sexist attitudes must be addressed at an early age with diverse, technology-based learning.

Spalding says the need for men, women, boys and girls, to work together without sexist attitudes must be addressed at an early age with diverse, technology-based learning.

She, like many women empowering others to succeed in their future, STEM-based or not, believes the future for girls in coding, calculus and chemistry will be strong.

“At the end of the day, if girls are interested in it, they should do it,” Guise said. “We are offering a way for girls to jumpstart their interest. It’s up to them to take that where they want it to go.”

Mark Evans | Mar 23, 2016 at 7:55 am

Great article–very in depth! Glad to see that Hagerty is bucking the trend and providing great opportunities for students.