“I just don’t know what to do. I have basically ZERO unibrow and I’m getting married tomorrow. I can’t let him see me like this!”

“You can borrow some of my Surma dye and paint it on, don’t worry! I’m sure it’ll look great.”

Though this conversation would be unusual to overhear in modern-day Florida, in 18th century Iran, lacking a unibrow was a serious concern…

Back then, it was just the beauty standard, meaning that girls’ insecurities reflected the ideals of the time. So though today many girls around the world feel insecure about their facial hair today, this was not always the case.

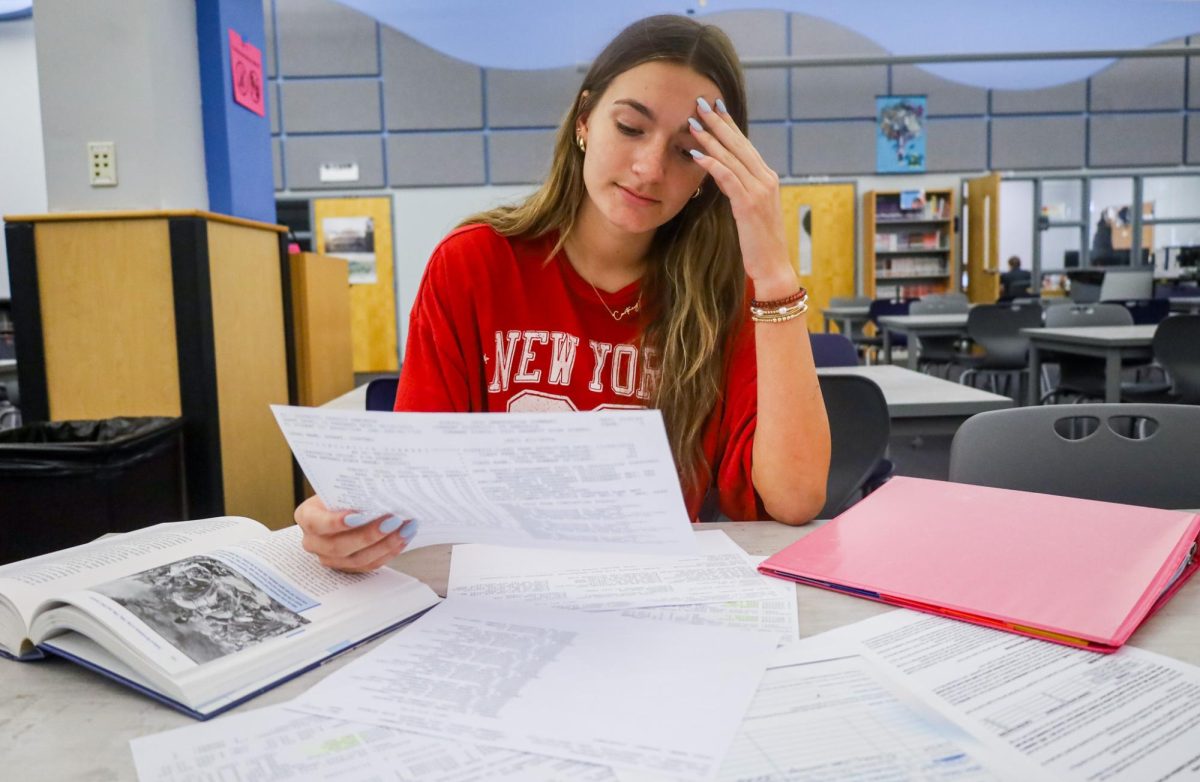

But if beauty standards are arbitrary and ever changing, why do they deeply impact the way many young girls see themselves?

“Pretty privilege” is defined as “a form of bias that gives preferential treatment to those perceived as attractive, according to social norms” (according to Very Well Mind).

So, on the surface level, being attractive may encourage others to do favors for someone or approach them in public. People may hold the door open longer, or strike up a conversation at the register.

This is an extension of the halo effect, which refers to the tendency of humans to attribute

other positive qualities (like kindness or friendliness) to individuals who already possess certain other positive traits, like attractiveness.

However, pretty privilege provides much more than a small boost in the social world. Several studies have linked attractiveness to increased earnings and confidence, and better mental health overall.

So it makes sense that women have been performing beauty rituals like shaving legs, plucking eyebrows and curling their eyelashes for centuries. Because being “ugly” comes with real-life consequences.

Junior Lana Major shared that there were noticeable differences in the way people interacted with her after she made changes to her appearance to better adhere to today’s standards.

“Nobody wanted to talk to me,” Major said. “[But afterwards], people just randomly came up to me, like, ‘Hey [do] you want to be friends?’”

Perceived attractiveness not only impacts how many friends one has, but also how their entire personality is perceived.

“I feel like if you’re more attractive, [for example], you can get away with being more silly,” junior Anna Sheldon said. “But if an unattractive person does something ‘weird,’ it’s looked down upon.”

Though pretty privilege also affects men, and statistically more so than women (monetarily, at least), average and unattractive women face a different set of challenges with the standard. Because women find attractiveness to be an expectation, and men find it a bonus.

According to a survey conducted by Dove in 2017, “[five] in 10 young females feel medium to high pressure to look ‘beautiful.’”

In addition, 70% of respondents from the same survey felt that there was “too much importance placed on beauty in defining happiness for females.”

“I feel like I have to look presentable, or else people won’t take me seriously,” sophomore Lily Karr said.

A study conducted by OnePoll in 2023 found that 62% of respondents believe that “as a woman, they are expected to live up to an unrealistic beauty ideal.”

And furthermore, 28% of women from the same study claimed that they first started feeling “body conscious” by the age of 16, an experience shared by many girls on campus.

“I’ve always been kind of big, and I used to just feel really insecure about that,” Karr said. “I would like to lose some weight, but I still think I’m beautiful.”

Karr is one of many girls on campus who experience body consciousness, which is not just about weight, but also height and body type.

“[My biggest insecurity is] probably my height,” junior Tiffany Nguyen said. “I have always wished I was taller, because I feel like I could [have] more of a [presence], if that makes sense.”

Not only have girls on campus reported feeling insecure, but they have also mentioned that their self-consciousness began early, some as early as their pre-teen years.

“It was awful in sixth grade, and maybe mid elementary school,” Karr said. “In those times, I was super insecure.”

Around this time, kids begin to become aware of how others perceive them and often make changes in hopes to fit in, leading them to compare themselves to others and internalize their peers’ comments.

In fifth grade, Major’s classmates teased her about the appearance of her blond, curly hair. Before she began styling it, her hair used to frizz up in the Florida humidity.

“I was called ‘Ravioli Head’ in fifth grade,” Major said. “People would be like, ‘Hey, Ravioli Head!’”

Comments like this motivated Major to learn how to style her curly hair, and even if the comments no longer bother her today, at the time, they deeply impacted the way she saw herself.

“I [used to think] I was ugly,” said Major. “[But] now everybody [is] like, ‘Oh, I love your curls.’”

Sheldon stated that even her friends contributed to her self-consciousness in middle school without meaning to. It was just the awareness of being different that had a negative effect.

“I feel like in middle school, comments that friends would make without necessarily trying to be rude still left an impact on me,” Sheldon said. “It definitely increased my insecurities.”

Though some girls, like Major, who made a change to their appearance, were able to gain confidence from the reactions to the changes they made, others, especially those who are insecure about things they cannot change, made peace with their insecurities as time went on.

“I think just accepting that you can’t change certain things about your body can really help,” Sheldon said.

Others were able to overcome their self-consciousness by focusing their efforts inwards, opting to work on their personality instead of spending energy on something that they could not control.

“I tried to put that effort into myself, when I was younger, as a person, and that [reflected] itself in how I view myself,” Nguyen said.

Also, some noted that cultivating their personal style helped them feel more comfortable in their own skin. Stating that by finding their own unique style, they found a new source of confidence independent of societal norms.

“Now, I just, like, take care of my [appearance]. I have a style that I actually [resonate] with,” Major said.

Nguyen echoed Major’s statement, emphasizing individuality’s importance in improving confidence overall.

“Outward expression is really important to me,” Nguyen said. “So, when I was younger, I tried to develop [my personal style]. Even though I knew I didn’t [fit the beauty standard], I felt good about myself.”

Though girls today may not be jumping at the chance to paint on a unibrow today, their insecurities still impact them in more ways than one might think.

And whether it is through developing a more concrete sense of self or gaining confidence by experimenting with their own style, students on campus have found all sorts of ways to cope with the ever-increasing pressure to always look their best.