Imagine a baby, fresh out of the womb, learning Algebra II; a toddler who, instead of learning numbers, is learning AP Calculus; and a fifth grader who is learning differential equations.

In the current survivor-style academic landscape, the pressure to be smarter, faster and more advanced than your peers is stronger than ever. But how much is too much when it comes to pushing kids ahead?

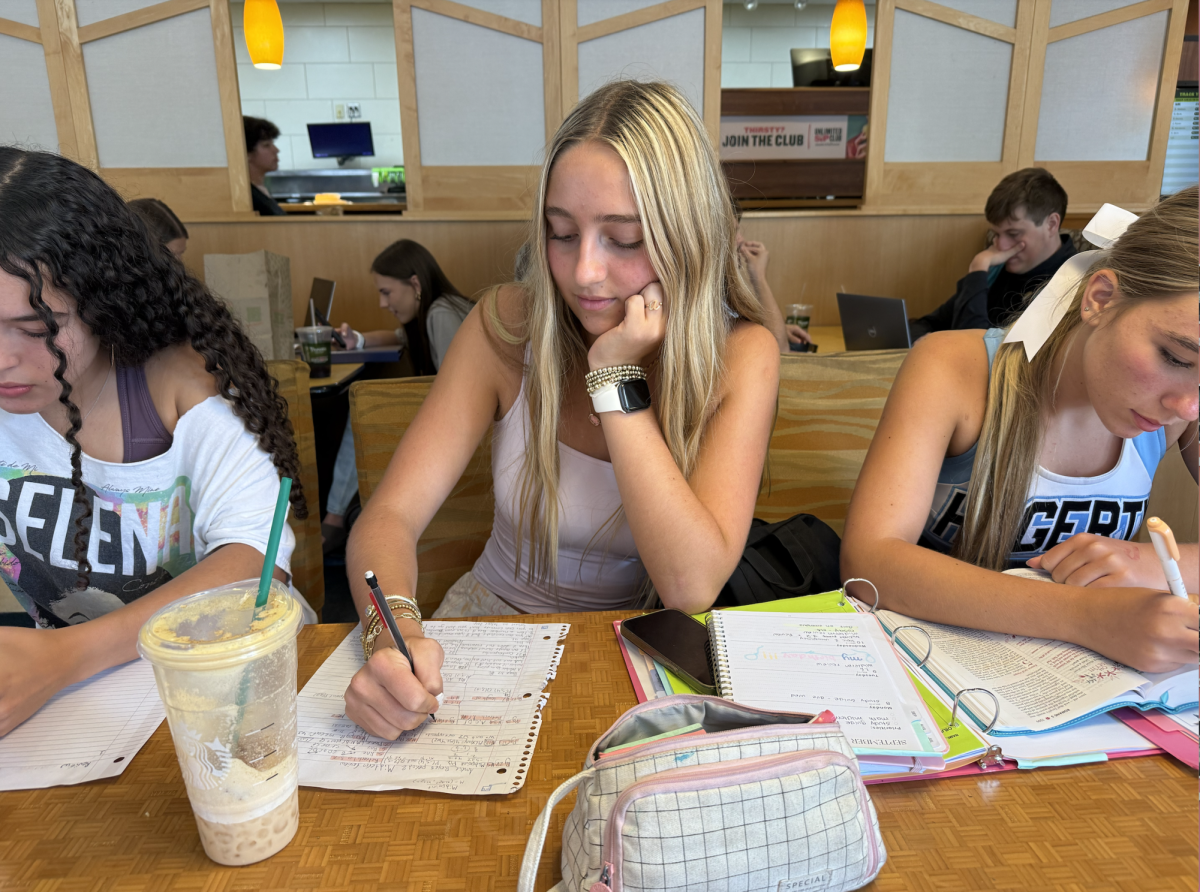

I have been victim to the need to be ahead of the others in my classes, of my friends. As an only child and a “gifted” student, the pressure was on almost immediately. The stress to always be better has led to endless nights of existential crises and habits that I am not always proud of.

My future, like many middle school students, has been planned out since seventh grade when I entered Algebra I. I would be in Geometry, then AP Precalculus, then AP Calculus, but then what? Unless you are going down a science or engineering path, AP Calculus is a more rigorous math course than most anyone will need. There remains a lack of truly useful math courses for juniors and seniors who are not pursuing math-heavy careers in the future.

Freshman year is the time to figure out your routine, where you fit in the school and who your friends are. It is the year of transition from a chaotic, immature middle-schooler to a responsible high-schooler. More pressure and responsibilities are placed upon your shoulders, making it harder to swim when you are thrown into the deep end of the math pool.

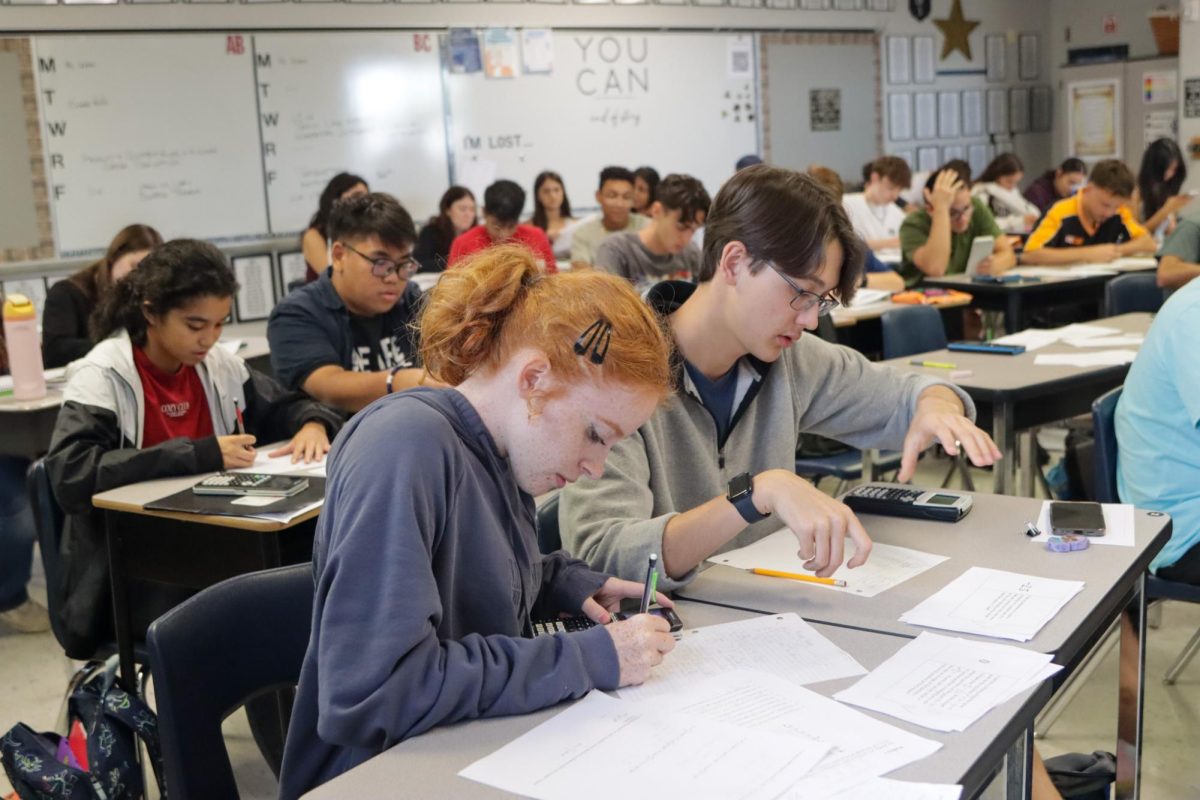

On the current path, all of these students are thrown into an AP class as a sophomore. AP classes in particular require extra knowledge, extra dedication and extra writing. With open-ended and extensive multiple choice questions, the classes seem daunting to anyone. I remember being terrified to face AP Precalculus, one part being the fact that there is an AP exam that is stressful and can change your college experience. But mostly, I was worried about how I would feel, and how I would be treated if I failed.

This constant pressure to be “ahead” goes far beyond the actual classes themselves and channels into a sense of self-worth. The feeling of being worthless when I didn’t earn good grades, or wasn’t one of the best in the class, especially in math, took a toll on my self-esteem. It has been an overwhelming stress dream in which my transcript was struggling against societal expectations (often because of my grade in math class) and allure true relaxation, every test a crisis about how it will affect my future.

Because so many have started their high school math careers years early, the students have created an even bigger issue for themselves: finding a math class that is both going to fulfill the additional credits that are required to graduate from high school, and not be so intense. For those who were pushed ahead, they might have to complete five, six, or even math credits instead of the usual four. However, there can be a struggle to find courses that go up that high. The race to be ahead does not end, it just moves to a higher, more stressful level each year.

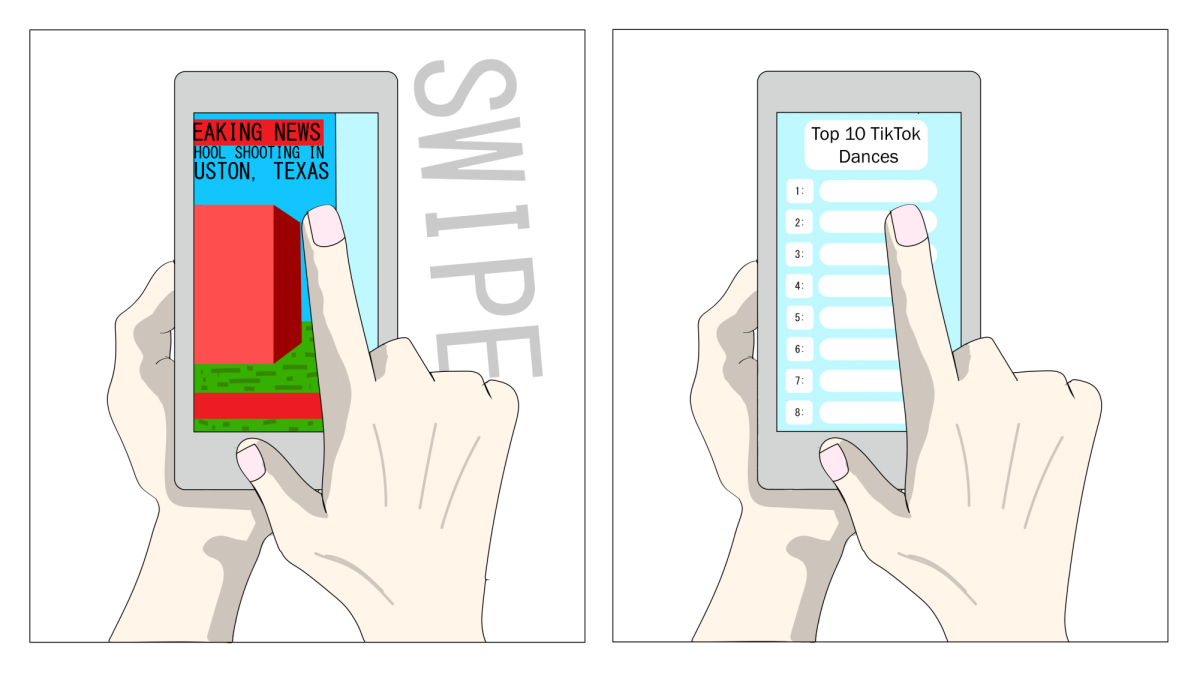

All this hustle and bustle makes you wonder; Are we really learning this because we love the subject or because it will help us in the future? Or are we just learning it to check off a box, to be ahead of everyone else?

The system itself has clear flaws. Schools generally encourage early acceleration in math because having “advanced” students looks good for their reputation. But when students like myself run out of new classes, then what? The very school system that pushed us to run faster is not always prepared for those who finished the race early. This is the same within the highly competitive nature of society today that cares more about advanced credits than their students’ well-being.

However, there are several things school systems can do. One thing they can do is to stop pushing kids so far ahead, and resolve the problem from the root. Or, as an alternative, they can add some less rigorous option for students deciding on a less math-heavy direction. Some classes utilized by other schools in the state are, for example, math for data and financial literacy. This class looks at data and the financial applications of high school math. It is an easier and more applicable class that students can use in the future, even if they don’t become scientists or engineers. Instead of normalizing students taking these intense classes, normalize being in simpler classes, or those that suit a student’s future.

The question is now, when is the crushing pressure going to be let up?