Introduction

Just over five years ago, students left for a week-long spring break but did not return—some for over a year and a half. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Florida schools in March 2020, schools extended the break for a week or two at a time…then another week…then another. After finishing out the year virtually, schools during the 2020-21 school year implemented a “hybrid” system, where students could either attend class in person or over video call.

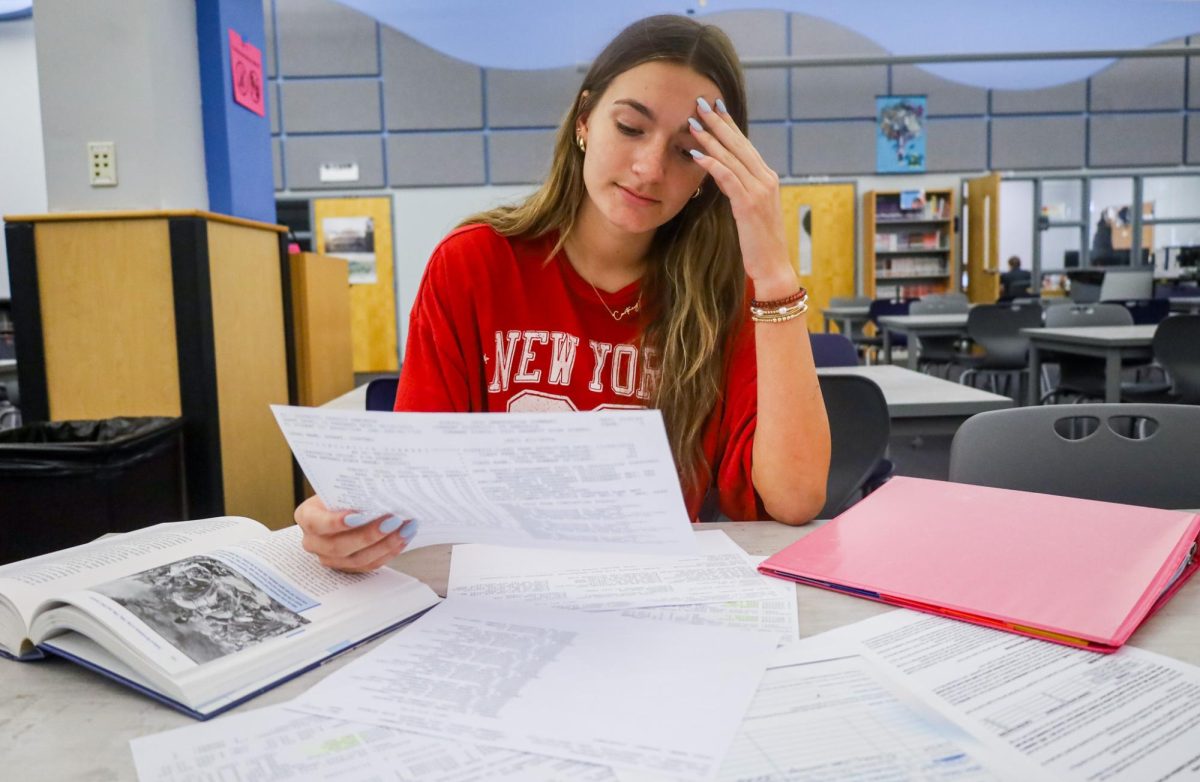

Though many now consider the COVID-19 pandemic over, its consequences and long-term effects persist. Current high schoolers, who went virtual as fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh graders, missed important developmental and educational events, which changed the course of their lives.

Social effects

According to the CDC, children between the ages of nine and 11 years old go through many changes regarding independence and identity, such as developing deeper friendships, gaining more awareness of themselves and their peers and distancing themselves from their families. The confinement and lack of contact that accompanied the quarantine significantly hindered students’ abilities to do any of these.

Since students had to stay home, many struggled to develop new friendships with peers that they could not interact with face-to-face. This was especially an issue for current freshmen and sophomores, who were in elementary school in 2020, and many of whom had limited or no access to phones and social media.

“I saw people in a Zoom call. That was about it,” freshman Alex Quiroz said. “Both my siblings [had] moved out by then, except my brother. I was definitely very alone for a while.”

Despite the constant struggle to maintain or form relationships in a time of isolation, some found ways around the barrier of distance. Students kept in contact over phone calls, group chats and social media, a phenomenon which could be linked to younger generations’ current overreliance on technology. As kids grew familiar with only communicating over screens, they continued those habits even after the quarantine was lifted.

“I used to be such an extrovert,” junior Kaitlyn Barry said. “I’d be talking to anyone I could see. And now I prefer the alone time. I like ‘just me’ time, just to breathe.”

Psychological effects

A study from the National Library of Medicine published during the pandemic found that the psychological impact of COVID ranged from widespread fear and uncertainty to individual cases of anxiety and depression. Despite the end of quarantine and the re-integration of virtual students into society, the mental health issues resulting from isolation and panic still persist for many.

A study published in the Cambridge University Press surveyed children and parents who had experienced a quarantine situation (unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic), and found that 25% of parents and 30% of children met the criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

With widespread quarantining leading to complete seclusion for many, one can imagine that children (many of whom are now teenagers) and families will remain affected by the pandemic for years to come.

Even to less severe degrees, some students noted changes in their own behavior. This includes increased wariness of others and heightened awareness of the dangers of disease.

“I’m definitely more of a germaphobe now,” Barry said. “[I] have to keep hand sanitizer on me. I always feel like I forgot my mask everywhere I go. And I start to notice more unsanitary things, like if I see people sneeze in the hall, then I’m like ‘Oh my God, I have to stay away.’”

Impact on teaching

During the pandemic, teachers had to adapt their educational style to fit an online format. For the end of the 2019-20 school year, this meant posting assignments exclusively online, receiving assignments digitally, and for some, conducting classes over video calls so that students could communicate directly. The 2020-2021 school year involved even more complications, as educators had to teach entire curriculums from start to finish in hybrid classrooms, in which some students attended classes in person, while others attended via video call.

Math teacher Gretchen Knoblach was teaching at St. Luke’s Lutheran School when the pandemic first hit, but soon transferred to Hagerty, feeling she had more to offer as a public educator.

“I really felt very good about my ability to teach math online,” Knoblach said. “I’d never done it before, and I do not consider myself a tech-y person, but I can learn. And I felt successful with it. I felt like my students were very successful. And for that reason, I felt like I could help by coming here and teaching things online, which I did. That was very difficult, but I felt like it was important.”

Though most students have now returned to traditional schools, teachers have kept many of the tools and techniques that they adopted during COVID. While they do not still conduct classes over Zoom, platforms like eCampus have thrived as a result of the shutdown. Virtual submissions have become the standard, and many teachers post digital resources or even allow students to contact them virtually if they need extra help outside of school hours. In the few years after the pandemic, Knoblach would set up meetings via WebEx for students who needed some one-on-one instruction.

“To this day, I still put absolutely everything that I do with my students on eCampus so that they can access it,” Knoblach said. “Had I not needed to do it during COVID, I’m not sure I would have ever done it. But I saw how with little effort you could make resources available to kids, so I just [kept] doing it.”

Impact on learning

“There was no online learning. There [were] online grades,” math teacher Dan Conybear said. “There was very little learning going on. And that, unfortunately, had a snowball effect when they entered high school.”

It is no secret that students struggled to learn during the pandemic. Not to mention the difficulty of disregarding the constant distractions and panic from news outlets and social media, even dedicated students had a hard time absorbing information in a completely new learning style.

“I don’t think I did [learn during COVID],” Quiroz said. “Just crammed everything, got it done, and did not care about it. So I don’t remember a single thing I learned, except for maybe how plants take in water.”

Disparities between accessible resources also came into play. In a traditional school, all students have access to the same materials, print-outs, computers, and extra supplies kept in a teacher’s classroom, but learning virtual forced everyone to rely on the supplies they had at home.

In a survey done by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 83% of high-performing students reported having consistent access to necessary resources for virtual learning, compared to only 58% of low-performing students.

Learning during quarantine also put a lot more responsibility in students’ hands. They had to manage their own schedule and appear for virtual sessions on time, instead of being herded from class to class by bells and teachers. They had to do all of their work independently rather than in a classroom environment, and they had to learn how to use digital tools without the assistance of a knowledgeable adult.

Barry used a calendar and whiteboard to keep herself on track, but saw that many of her peers struggled to retain information learned virtually, even when they returned to in-person school the following year.

During quarantine, little had prevented students from cheating or looking up answers, and often teachers took few—if any—steps to discipline those they caught.

“I remember eighth grade when we all finally all came back from being virtual or hybrid,” Barry said. “There was a lot more struggling, because no one could really cheat on assignments. I noticed when people came back, they lost that resource, and so they lost that familiarity [with] the subject.”

This trend shows in standardized test scores. For eighth grade, average math scores decreased steadily after 2019, going from 279 (2019), to 271 (2022) to 267 (2024). The same happened in reading comprehension scores, which decreased from 263 (2019), to 260 (2022) to 253 (2024). These drops could result from a multitude of factors, but considering that reading scores from 2020 to 2022 dropped more than they have since 1990, and math scores from 2020 to 2022 dropped for the first time ever, the link to the pandemic is undeniable.

“I think math [took] a huge hit during the pandemic, and my guess is it might be the biggest area of difficulty for students,” Knoblach said. “What I’ve witnessed in the five years since is that students who seem very capable of learning come to our classes, not quite at the level that I would have expected, had they not been impacted by COVID.”

Knoblach pointed out that many of the foundational algebraic skills, which students should have learned during the years they were quarantined, are some of the most major gaps in students’ knowledge today. These skills can be very difficult to learn through a virtual platform, especially since math teachers were relatively unequipped to teach virtually in 2020.

“The things that my Algebra I students struggle with are the same things that the [Math for Data and Financial Literacy] and the Calculus students struggle with,” Knoblach said. “So it looks like [during the years of COVID], there were just many things that—although they’re not difficult concepts to learn or to teach—they simply weren’t understood at the level that kids need.”

Some teachers find hope going forward. Students who dedicate themselves to making up for what they missed can do so, and many teachers at Hagerty set aside time after class to help those who need it.

“The kids that are graduating this year and will be graduating over the next several years, I would expect to be even more negatively impacted by COVID than the students we’ve seen in the previous five years,” Knoblach said. “So I think teachers and parents and students all need to understand that for the next five or more years, it’s going to be more important than ever to give students the extra [help] that they need, and through no fault of theirs, likely didn’t get.”

However, these next few years will likely involve many struggles for those who do not receive this support. The pandemic—while technically over—can still be seen in the gaps in education that it has left behind.

“It’s asking a lot of a high school student to take the initiative themselves and catch up on the learning they’ve missed,” Conybear said. “It takes a lot of personal commitment to want to learn that subject, instead of just wanting to get the grade and be done with it. From a student’s perspective, you want to be done with the class and move on. They can learn it on their own if they really want to, with the help of technology, but that’ll rarely happen.”

adriana | May 23, 2025 at 8:48 am

wow, whoever wrote this is so amazing and a great writer. im so glad they’re editor in chief for next year