In movies, cheating involves elaborate hand signals, notes stuffed in shoes and answers scribbled in the crook of a forearm. In reality, cheating is as simple as hitting Ctrl-C and Ctrl-V.

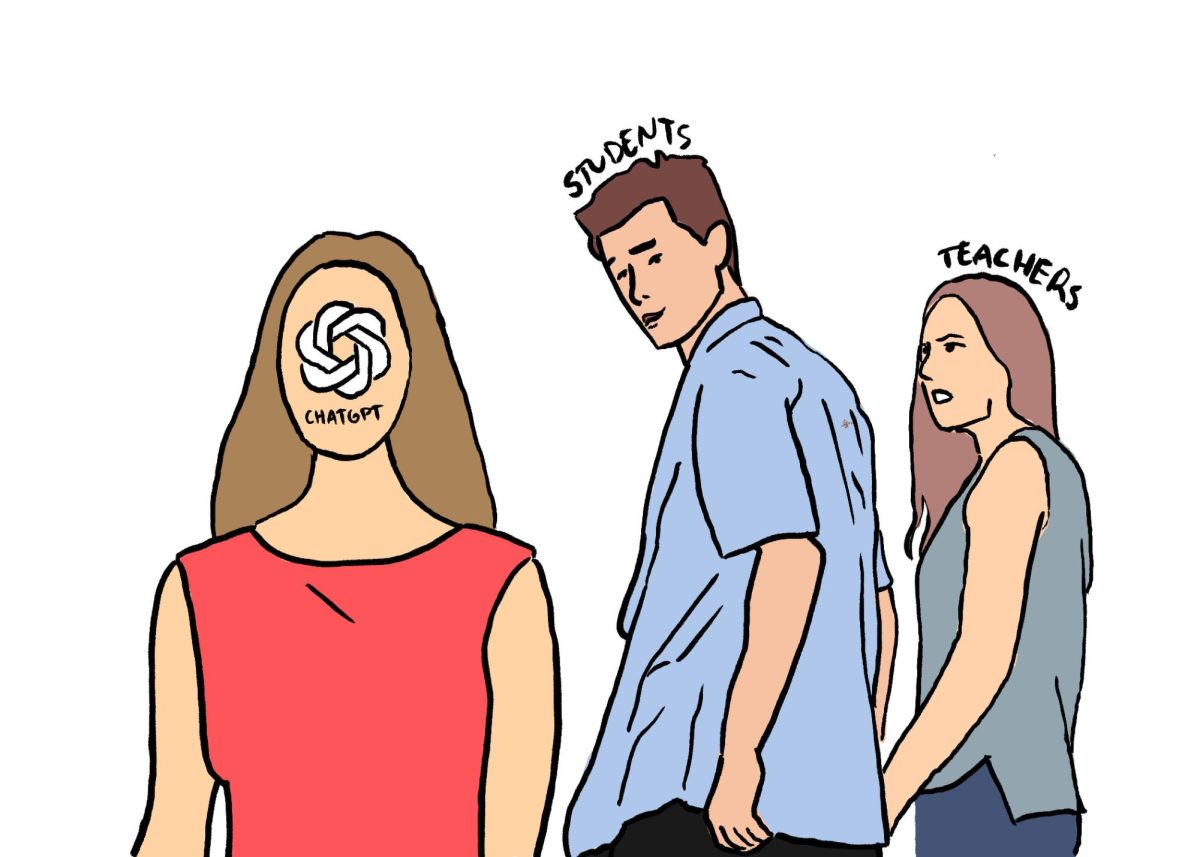

With the rise in AI technologies, cheating has become even more accessible, causing teachers and administrators to debate how to best tackle the issue. But cheating has always been a problem.

The real question is not how to reduce cheating–it’s how to displace the attitudes that condone it. We could debate the effectiveness of sites like Turnitin.com, the severity of punishments, the need for greater teacher supervision–but that wouldn’t tell us why students cheat in the first place. To target the fruit but not the root is a fool’s errand.

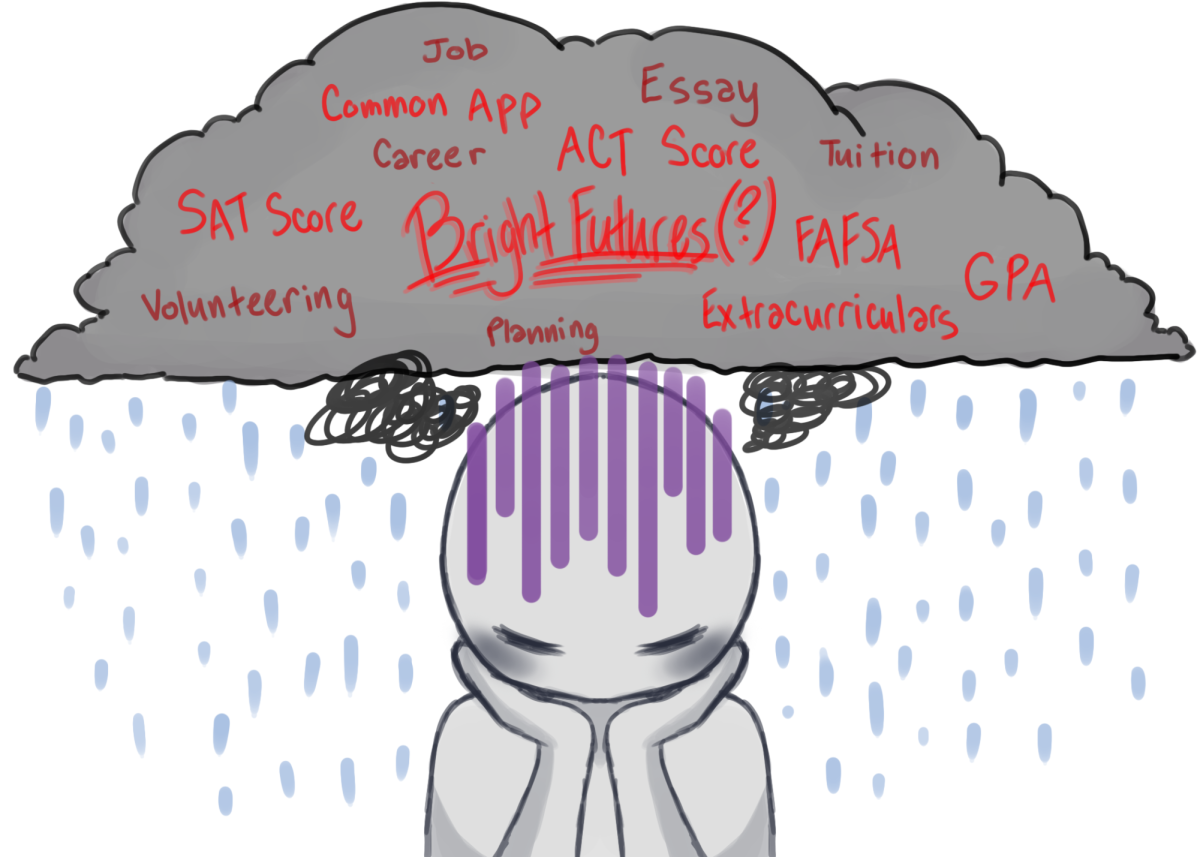

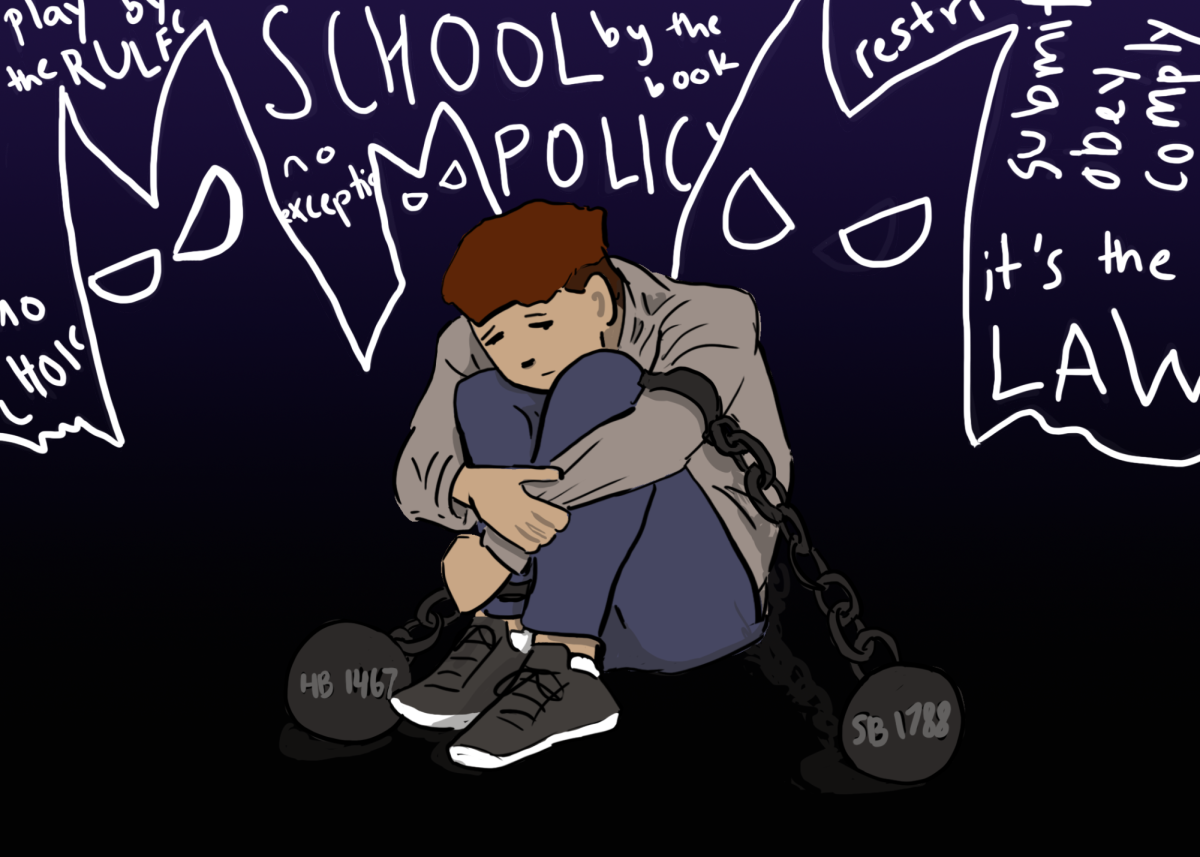

Looking at the jump in cheating from elementary to high school, the easiest explanation is increased pressure. From pre-K to eighth grade, school is relatively care-free. Long division is most students’ biggest worry. But when high school starts, suddenly grades are all that matter. College admissions, GPA, class rankings—all of it funnels into an overwhelming pressure to succeed. As the stress increases, students find their moral code less binding.

Slowly, “it’s just one time” snowballs into many more. With the desire to upkeep appearances in front of teachers and peers, some students feel that they will be left behind if they don’t cheat in order to get the grade. It’s just using their resources, right?

Students’ sense of justification only increases as they discover their peers cheating as well. A survey done by the Educational Testing Service found that 75% of high schoolers admit to cheating at some point in their school careers. Even those who don’t cheat are not likely to report instances of cheating, for fear of being a “snitch” (a label that in recent years has become worse than being called a cheater). With a community-wide sense of permission, students excuse their guilt easily.

The problem is only exacerbated when students see that cheaters often go uncaught, and even when they are caught, not punished severely. Without the threat of consequences, students feel no obligation to follow the honor code. In addition, the bureaucratic process needed to hold a student accountable can discourage many teachers from following proper procedure, as they too wonder if cheaters get any consequences other than a slip of paper and some detention time.

The question now is: what can we do about it? Many articles online point the finger at teachers, arguing that they should make their curriculums more engaging and focused. While certainly, allowing the students to be more in charge of their education would decrease student apathy and their desire to cheat, students need to be held accountable too. There needs to be a mutual understanding that school is about education, not grades. We need to put in the work instead of taking the easy way out.

Complicating the issue, online classes add a whole new factor into students’ ability and tendency to cheat. First of all, FLVS is an accomplishment not many states can boast. To be able to take state-accredited classes online if chronically ill or homeschooled is a wonderful outreach to often-overlooked families in those situations. However, the problem, as with many things, is overuse. These days, most students see FLVS and SCVS as an easy A for the same GPA boost. The bar of entry is too low, and the temptation too great.

Brick-and-mortar teachers shouldn’t have competition. They shouldn’t have the constant worry that if they push too hard, their students will switch to online. They shouldn’t have a voice that tells them to turn a blind eye to cheating so they can still have a job next year.

But they do. And that’s not right.

Cheating is everyone’s problem. As cheesy as it sounds, students are the future of America. When cheating becomes the norm, students don’t learn, teachers miss out on why they joined the profession in the first place, and education is an exercise in going through the motions.

The first step to a solution? Acknowledging there’s a problem. The more we try to ignore it, the greater the issue, and its effects, will get. Let’s have a real conversation—students, teachers, parents, school administrators, lawmakers, everyone—and make a plan to end this atmosphere of indifference.