Anyone who talks with junior Jiana Velez would assume English was her first language, but as a Child of Deaf Adults, Velez’s first language was American Sign Language. Velez did not grow up hearing English so learning to speak did not come without difficulty.

“For deaf people, it’s not really easy to pronounce words, so it was all about getting a speech therapist,” Velez said. “That happened for most of my siblings.”

Family life

Raised by multiple generations of Deaf family members, Velez and her three younger siblings are all fluent in ASL. Due to this, Velez faces many difficulties in translating for her family.

“Since I’m the oldest sibling, I’m usually depended on to interpret for a lot of things, like important meetings,” Velez said. “ It can get stressful and frustrating, especially because CODAs don’t know every word in sign language, so whenever you don’t know a word, you have to describe it or fingerspell it.”

For sophomore Amin Nouri, interpreting is a way for him to connect with and support his family.

“Nothing [feels] better in the world than being able to help my parents with something that they were having difficulty doing,” Amin said.

Having grandparents from Iran, Amin and his sister Vida switch between three languages daily to communicate with their family.

“Home life is a mixture between speaking to my hearing siblings, a mixture of speaking Farsi to my hearing grandparents, and speaking in sign to my father and my mom,” Vida said. “Because my grandparents actually don’t know sign, there is a lot of translation going on. So it’s an interesting mix of just a bunch of different cultures and languages going on at the same time.”

Residing in a gray area between the hearing and Deaf worlds, Vida constantly faces the question of which one she wants to represent.

“When I was younger, being seen as part of a different culture, [I often asked myself] does that make me stand as an outcast to hearing society?” Vida said.

Vida had been conscious of the differences between hearing and Deaf cultures since she was a child when others found her family’s customs strange.

“As a child I really disliked when my parents would sign to me,” Vida said. “I was definitely more ashamed of it. I guess that comes with the aspect of being a child and being uneducated about what being deaf meant. But now, I am proud of being a CODA and being able to inform others about the difficulties of a culture that sometimes has trouble communicating with another culture.”

ASL class

CODAs are not new to Hagerty. Graduate Carter Wegman was born to Deaf parents and acted as the president of the ASL honor society in 2022-23. CODAs have been a staple of the ASL program since shortly after it’s conception.

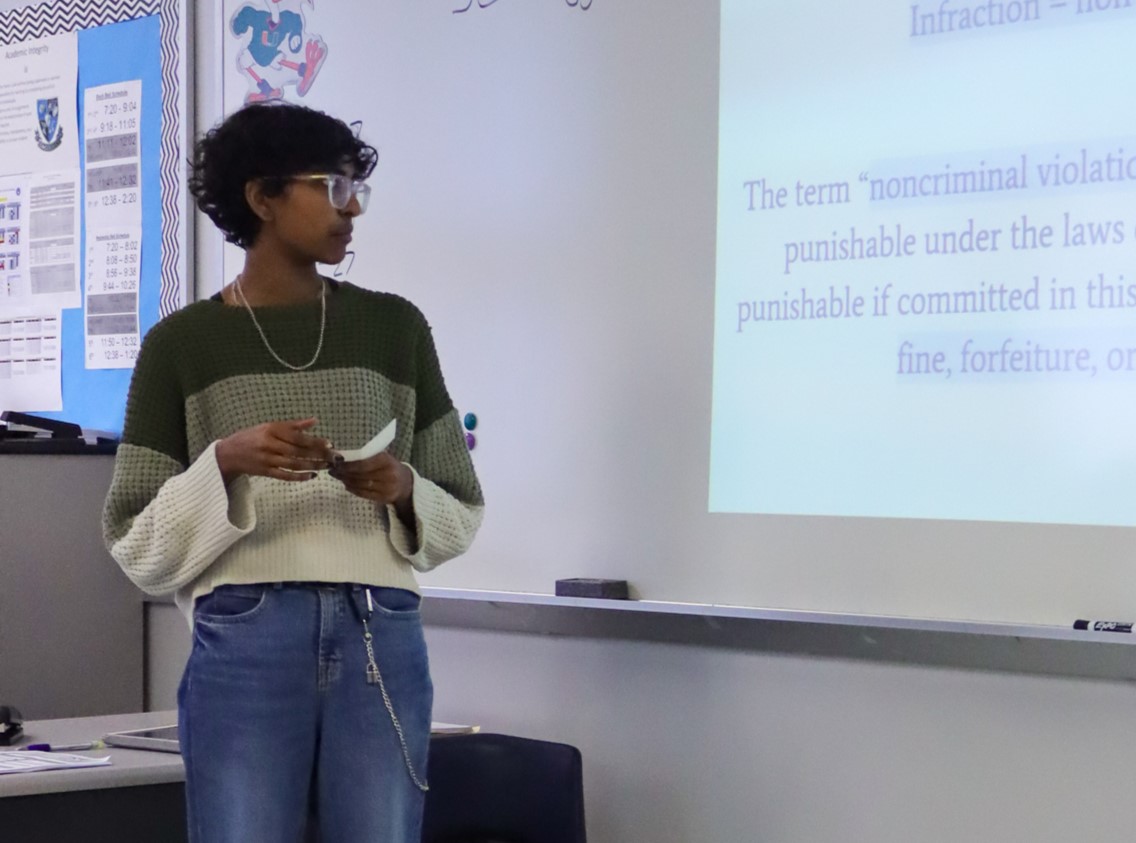

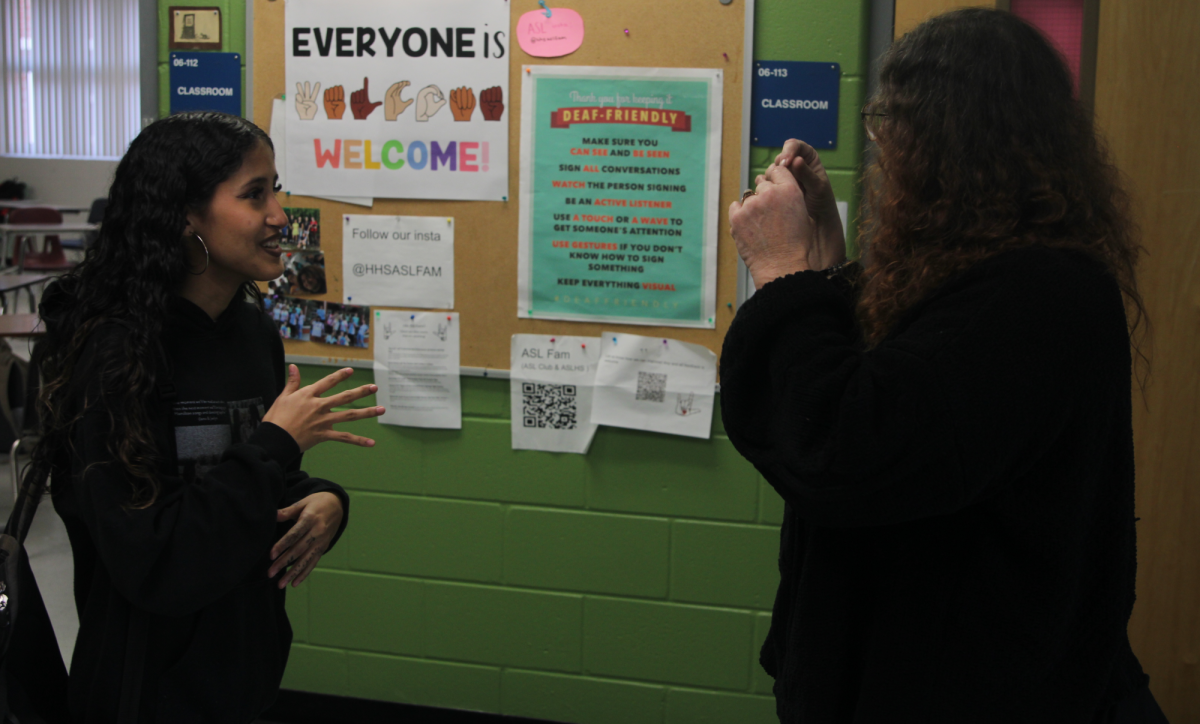

Vida, Amin and Velez are all enrolled in the ASL program where they interact, teach and share life experiences with their classmates.

“The awesome part is the CODAs have someone to relate to and realize they are not alone,” ASL teacher Barbara Chaves said. “Although the [CODAs] are proficient, they learn variation of signs, ASL grammar, Deaf History, Famous Deaf people, Deaf Culture, and networking.”

While not learning ASL from scratch, the ASL class helps Vida discover new facts about the history of the Deaf community.

“I’m super appreciative of the fact that I can learn more about Deaf culture with my classmates,” Vida said. “I personally feel that much of the content relates to me especially on a deeper level.”

Being native to signing, sometimes CODAs need to resort to more basic signs in order to communicate with those who are still learning.

“Being in an ASL classroom, because [my classmates are] not 100% fluent yet, it’s more like a code switch for me,” Velez said. “We have to code switch to make sure that the students understand what we’re saying.”

Misconceptions

Beyond signs, many hearing people struggle with comprehending the reality of being Deaf and attempting to find others with shared experiences.

“The Deaf community is much smaller than the hearing community because it’s not everyday when a deaf kid gets born,” Velez said. “It’s a very rare thing.”

Due to the small size of the deaf community, there is a lack of understanding of the Deaf identity from hearing people. For Velez, many people underestimate her family’s ability to comprehend information because of their lack of hearing.

On one occasion, Velez was interpreting for her father with a salesman. When her father asked for more information, the salesman handed her the paper for her to explain to her dad.

“He [gave] it to me because he thought that my dad couldn’t read,’ Velez said. “He can read—he’s a grown adult.”

This is not the first time Velez had experienced ignorance in regards to Deaf people. Others had asked her how a Deaf person knows if someone is yawning or screaming.

“That’s the dumbest question ever,” Velez said. “ It’s obvious by a person’s facial expressions and how slow a yawn is, that it’s a yawn and not screaming for death. It’s the simplest common sense question.”

In addition to the assumptions made by hearing people, many underestimate the communication boundaries Deaf people face daily.

“I think from a hearing perspective, it is going to be difficult to understand that the Deaf and hearing world are actually different, and the hardest part would be accepting those differences and overcoming them,” Vida said. “Some hearing people [are] unaware of the difficulties of communication with Deaf people, and when it comes to communication especially, that is a huge obstacle that many can’t overcome.”

To a CODA, their identity and place in the Deaf community is an important part of their identity and gives them valuable experiences and joyous memories.

“To be a CODA means so much more than just having deaf parents,” Vida said. “Being a CODA means being immersed in a Deaf community, just an entirely different culture beyond the hearing realm.”