Crumbl Cookies has taken the internet by storm, with its weekly flavor menu captivating social media creators and audiences alike. But more concerning than the millions of people spending $4.49 on a single cookie (without tax) is the fact that for every Crumbl order, be it in-person at self-serve kiosks or online through the app, the company asks for a tip–with the default set to $2, a whopping 45%. Considering the average Crumbl experience consists of ordering at a machine and only interacting with workers as they bring out cookies, the internet’s acceptance of it all begs one question: what are people really tipping for?

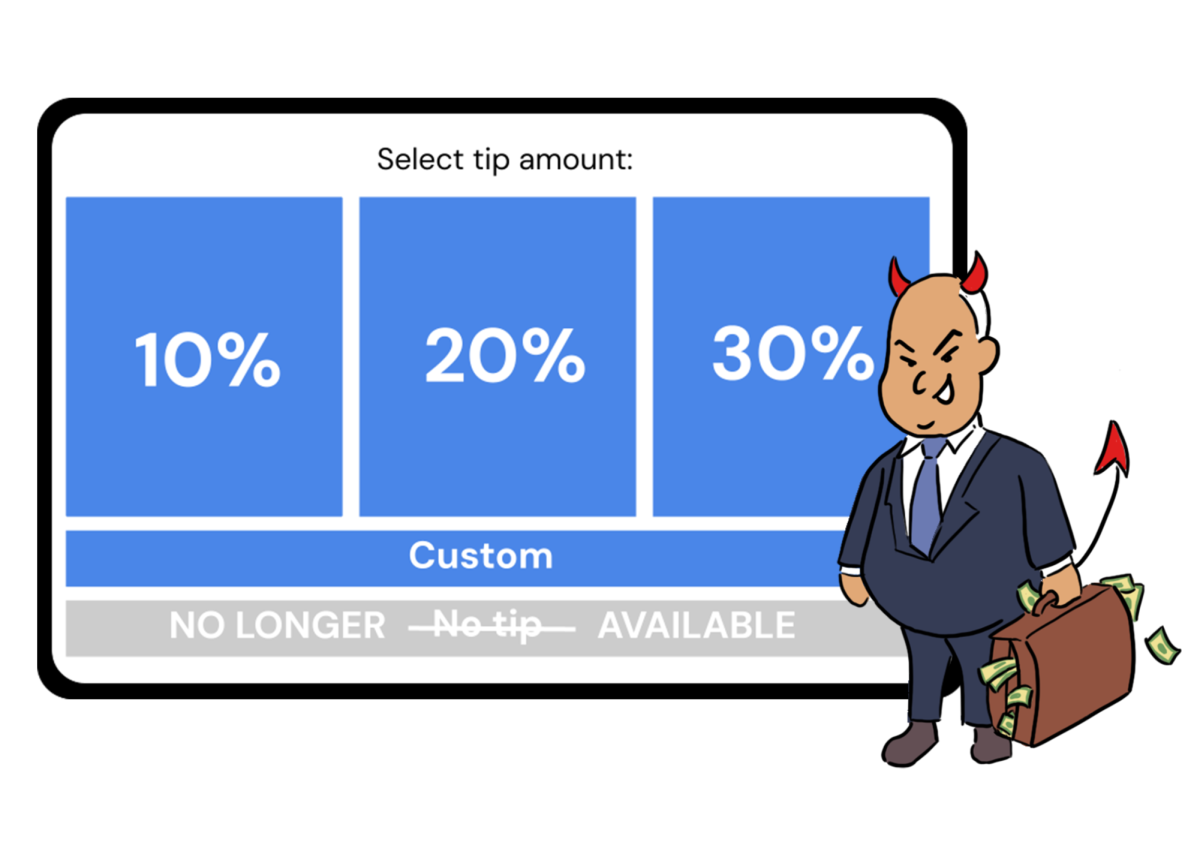

The problem is not so much in tipping itself. Brought by American travelers returning from Europe after the Civil War, tipping served as an extension of gratitude from customers to exceptional service workers. However, in a time where mobile ordering and self-serve registers are the norm at airports, coffee shops and stadiums, companies have misconstrued the practice, rendering it a money-making scheme rather than a statement of thanks.

It is one thing to hand a crisp $20 bill to the waiter patiently taking orders, refilling drinks and listening politely to lengthy family stories, but tipping a machine simply has no point. Are customers tipping to replace its batteries? Tipping so it can get the newest high-tech screen protector? Or, in reality, are companies just using Americans’ tipping guilt to their advantage?

Americans are the biggest tippers in the world: coming in at an average of 13.4% gratuity at dine-in restaurants, they easily beat the second-highest tippers, the United Arab Emirates, at 8.2%. Looking at Europe, the gap widens even more drastically, with American tips amounting to triple that of Sweden and Britain, according to a Yougov study.

Tipping culture is not just etiquette in America—for many service workers, it is the difference between a hot meal and an empty stomach. The federal minimum wage for tipped workers is currently $2.13. This means corporate higher-ups can intentionally and legally shift the responsibility of paying workers from themselves to customers. Knowing this, it is no wonder why Americans are so heavy-handed with their tips.

However, unlike tips handed to human workers, which are protected by the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, tips given to machines are not guaranteed to make it into the hands of workers. In other words, the 75% of remote transactions that ask for tips are not asking for workers; companies can keep that money for themselves, negating the whole point of a tip.

Society is bound to only get more and more technologically minded. Since 2015, Panera has implemented touchscreens in most of their franchises; McDonald’s is currently in the process of rolling out the technology. The self-serve kiosk is here to stay, and some may argue it is for the better in terms of convenience and cost efficiency. Regardless, it is important for us to set ground rules in place now, before tipping culture extends to the automatic door as well.

All good things come in moderation—tipping included. Paying robots was never, and should never be, the face of American tipping. Gratuity should be an active choice, not an automatic expectation.