Imagine devoting your whole life to one thing enough to be called an ‘expert,’ reaching the point to where you can apply your knowledge as you see fit. A cardiothoracic surgeon would have the knowledge to improvise on their own and make decisions based on the absurd amount of years grinding away in medical school.

Now imagine someone with far less knowledge on the subject coming in and messing everything up. The guy who owns the hospital walking in during the open heart surgery and telling the surgeon how to do their job.

What is the Chevron deference?

That is essentially what the Supreme Court accomplished when they overruled the Chevron deference in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, except the consequences apply to all federal regulations, from food to education, to literal toxic waste.

In 1984, the Supreme Court established the Chevron deference in a ruling for Chevron USA v. Natural Resources. The Chevron deference stated that federal agencies should have more power when it comes to interpreting laws related to their field, since they have a wealth of knowledge in their chosen subject. When cases arose, the courts looked to them for help interpreting vague laws. Congress was able to pass “bubble policies” that gave these agencies plenty of room to adjust and interpret rules as they see fit, since the in-house experts know how to best tackle difficult problems specific to them. This ruling has impacted over 18,000 different cases in every area of law.

The ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo on June 18, now undoes all of that. Instead of congress passing the “bubble policies” for the agencies to interpret their own regulations, the court now interprets any vague laws or inconsistencies.

Why was the Chevron deference important?

Federal agencies dictate most aspects of life and safety. The Food and Drug Administration makes sure our meat is not actively rotting; the Environmental Protection Agency makes sure we do not die of radiation poisoning; the Department of Health and Human Services tries to prevent us from dying from unbacked medical procedures and ensures we can recover from medical and public emergencies.

Suppose Congress wanted to limit harmful benzene emissions (benzene is found in glues, adhesives, cleaning products, etc.). They would simply make it clear to the EPA that something needed to be done; they would not write the precise formula to determine how much benzene is safe under certain circumstances—because that would be ridiculous. Imagine having to know literally everything. And it still would not be as accurate as the measurements of actual scientists who have been working in the field for their whole lives.

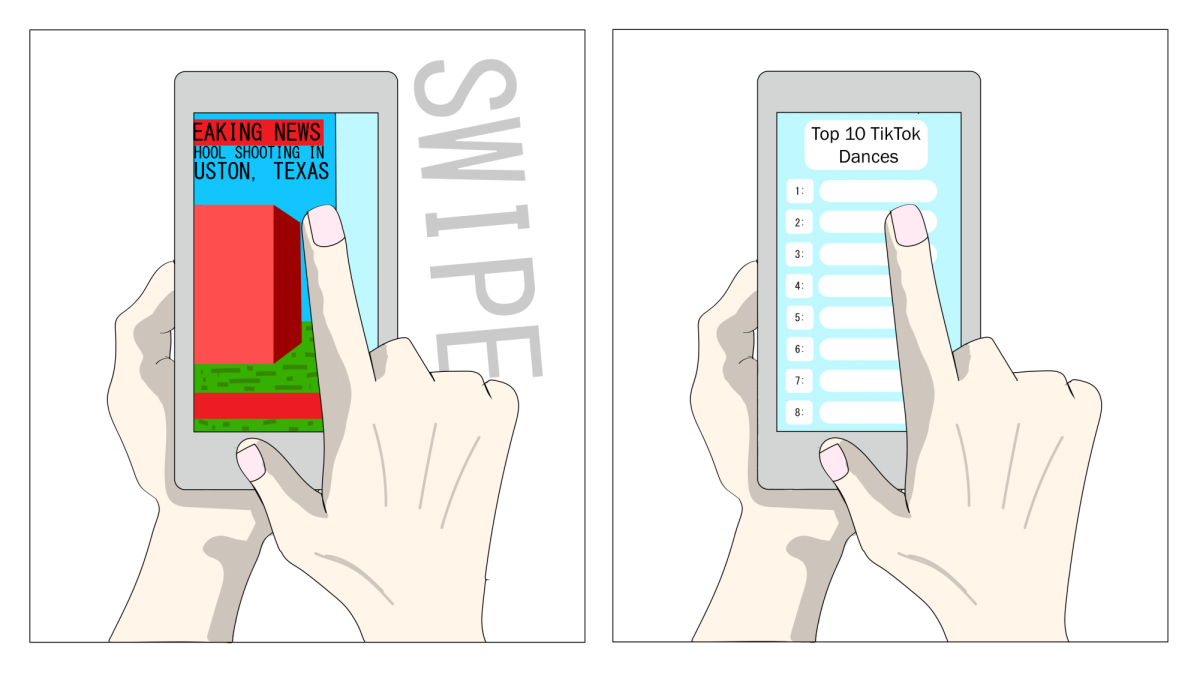

And now, with Chevron overruled, guess what? Instead of those experts having a majority say in how complex industry decisions are made, it is a bunch of people who went to law school.

At first look, it may not actually sound too bad. After all, interpreting laws is the court’s job, so why shouldn’t they have more of a say when it comes to the regulations that impact everyday life?

If the guy owns the hospital, why shouldn’t he give instructions on how to use the space?

Why not trust the courts with this?

There are hundreds of different niches of regulations: finance, energy policy, education, labor, consumer protection, the environment, health care, housing, food and drug safety, law enforcement—the list is endless.

How can we expect anyone to have enough knowledge of even four of these subgroups to properly regulate them?

We can’t.

There have already been some embarrassing slip ups caused by the Supreme Court. Justice Neil Gorsu confused nitrous oxide (laughing gas) with nitrogen oxide (a smog-causing emission), which when written in law could have had disastrous effects if not caught in time. Someone who mixes up basic chemical elements shouldn’t be regulating them.

In one particular instance, Justice Samuel Alito—one of the four justices who voted against Roe v. Wade—could not even pronounce “mifepristone,” one of the two drugs used in medical abortion, then suddenly claimed it to be harmful, despite overwhelming evidence otherwise. According to Vox, “patient deaths due to the drug are lower for mifepristone than they are for Tylenol, penicillin, or Viagra.” This kind of attitude not only shows a massive level of incompetence, but also immense bias from his personal beliefs.

The Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo case—the one that got Chevron overturned—is even stranger: The National Marine Fishing Services has to let federal observers collect data and prevent overfishing. The NMFS requires that the fishing industry and domestic boats be the ones to pay for the salary of these observers. The industry argues that the federal agency is misusing its power against fishing companies.

The Biden Administration not only shut down the program, but refunded all of the money back to the fishing industry, so that there would be, “no live controversy anymore.” And for some reason this was the case they used to overturn Chevron? If anything, shouldn’t this case show that Chevron worked? Yes, NMFS overstepped, but the executive branch rectified it. Even if it had not been rectified, one agency making a mistake should under no circumstances justify the complete upheaval of the system. They applied a case about a fishing program to medicine, nuclear energy, food and everything else.

So again… just why? Well, let’s see: it puts regulatory rights in the hands of the court and out of the hands of actual experts in places like food, health, climate…

Who this ruling really benefits

One of the biggest advocates for the overturning of Chevron is fossil fuel billionaire Charles Koch. Alongside his brother, Koch is one of the richest people in the world, with six global conglomerates companies under their family name. Coincidentally, both brothers are very against the existence of climate change, spending, “$145,555,197 directly financing 90 groups that have attacked climate change science and policy solutions, from 1997-2018,” according to a GreenPeace report.

Coincidentally, Justice Clarence Thomas has attended at least two Koch donor events, serving as a ‘fundraising draw’ for an organization that regularly brings cases before the court. He defended himself by saying it was an act of, “personal hospitality,” and not worth reporting. However, at least in my book, “personal hospitality” means lunch at someone’s house, not an all-expenses-paid nine-day yacht trip.

In 2005, Thomas was actually in support of the Chevron doctrine, even writing up a landmark Supreme Court opinion upholding the doctrine. However, his opinion seemed to have drastically changed in recent years, conveniently after receiving “decades of luxury travel” from billionaires Paul Novelly, Wayne Huizenga, David Sokol and Harland Crow.

Following Thomas’ footsteps, Justice Alito was flown on a private jet to Alaska, which, according to ProPublica, would “have exceeded $100,000 one way.” Who was the benevolent host that paid for the trip? A gentleman named Paul Singer, a hedge fund manager who has had ten cases before the court. Naturally, Alito did not include this trip on his disclosure form either.

Of course, he did not face any consequences for this, despite giving more insight as to how seats generally work than actual justification for his actions. The various rules regarding ethics do not really apply to the Supreme Court, seeing as they are regarded as the highest form of law. In extreme cases, Congress can impeach a justice; however, that rarely happens.

To think the judges are still able to remain impartial is absurd. Not only is Chevron taking the future of our environment, health overall wellbeing out of the hands of experts, but it leaves it susceptible to immense corruption.

These are the moral standards that justices are held to. Additionally, these bribes can have disastrous consequences for our environment. If justices now have the power to interpret regulations, and there’s nothing to stop big corporations and elite billionaires from paying them off, then we’ve essentially given up our power to billionaires, who almost never have our best interests in mind. The overturning of the Chevron Deference is a huge judicial power grab that takes power away from the people who actually know what they’re doing.