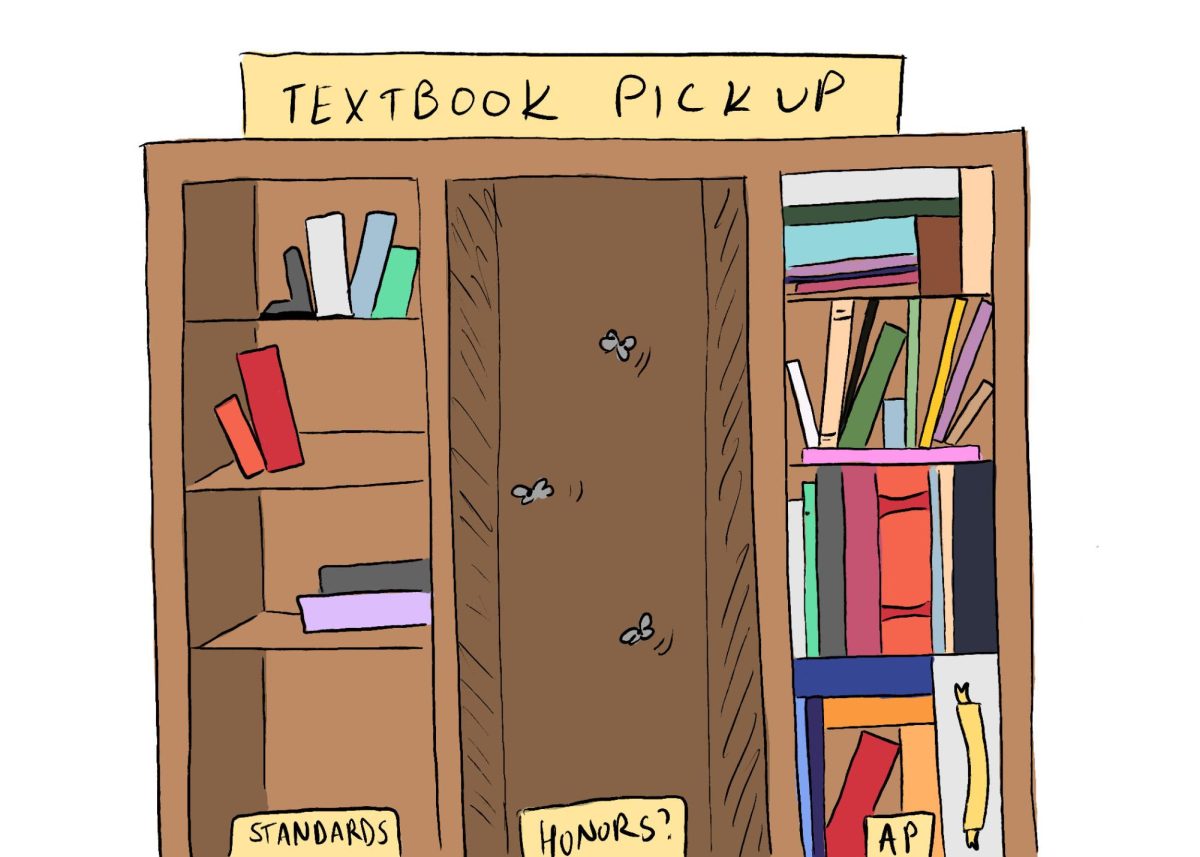

Step into the classroom of a Standard class and you will see basic worksheets, online readings, and kids slumped over in their chairs. Step into an Honors class and you will see the exact same thing.

The gap between Honors and Standard classes—in terms of rigor, focus, and comprehensiveness—has gotten smaller and smaller. In theory, Honors classes should provide an in-between option for students who want to gain a deeper understanding of a subject, with peers who also seek advanced knowledge, but without the workload or stress of an AP class.

In reality, they are more like Standard classes with a GPA boost.

Part of this issue stems from the fact that no one can quite define what constitutes an Honors class. The course guide describes most Honors classes as more “rigorous” or “in-depth”; these subjective adjectives make it pretty difficult to quantify exactly what makes taking an Honors course worth the 4.5.

Additionally, no national, statewide, countywide, or even schoolwide standard exists for exactly what material an Honors teacher should cover as opposed to a Standard teacher. Most of the time, students have no idea what they should prepare for when signing up for a “more advanced” class because the school system so far has never exposed them to a consistent level of difficulty among teachers of the same level. And certainly, giving educators the chance to adapt the curriculum for their teaching style and their students’ learning needs always leads to a better outcome than needless interference from the government or administration. But a general consensus of ways that teachers can differentiate Honors classes from Standard ones—or even a better definition of the word itself—would help.

The problem does not stem from teachers, however. And it is not that students are inherently unintelligent and lowering the standards for their classmates—in fact, far too many belittle their own intellect. Rather, there is another issue at play here.

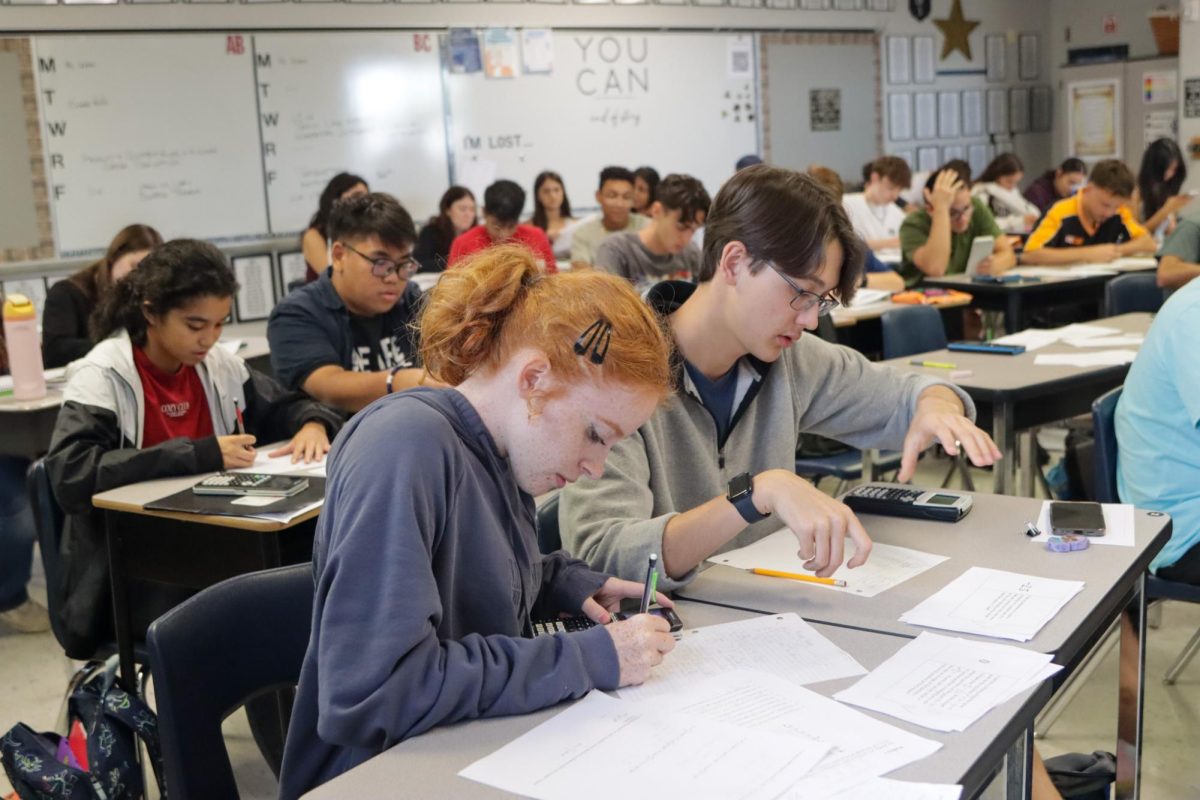

“There’s negatives and positives to taking Honors classes,” English teacher Rachel Copley said. “They might be overwhelmed with the work as a negative side of it, or they might not feel confident in their ability to complete the work, which is obviously a negative. However, it’s always going to be a positive to push yourself to do more. Anybody who is willing to apply themselves could be successful in Honors.”

Standards for Honors classes deteriorate when students are not willing to apply themselves. For some reason, many have difficulty grasping the concept that Honors classes do require work and thought.

“In a Standard course, [you] have to feel out how you have to go,” Copley said. “So that’s not even to say that you go at a slower pace by any means. You just go more with the flow of the class. As opposed to Honors, [in which] the students really need to go more with the flow of the curriculum.”

If a student expects the curriculum to change for them, or an easy “A” from writing a few incomplete sentences, they would be better off in a Standard class. And that is not necessarily a bad thing; many do seriously benefit from the flexibility and extra help offered by Standard classes.

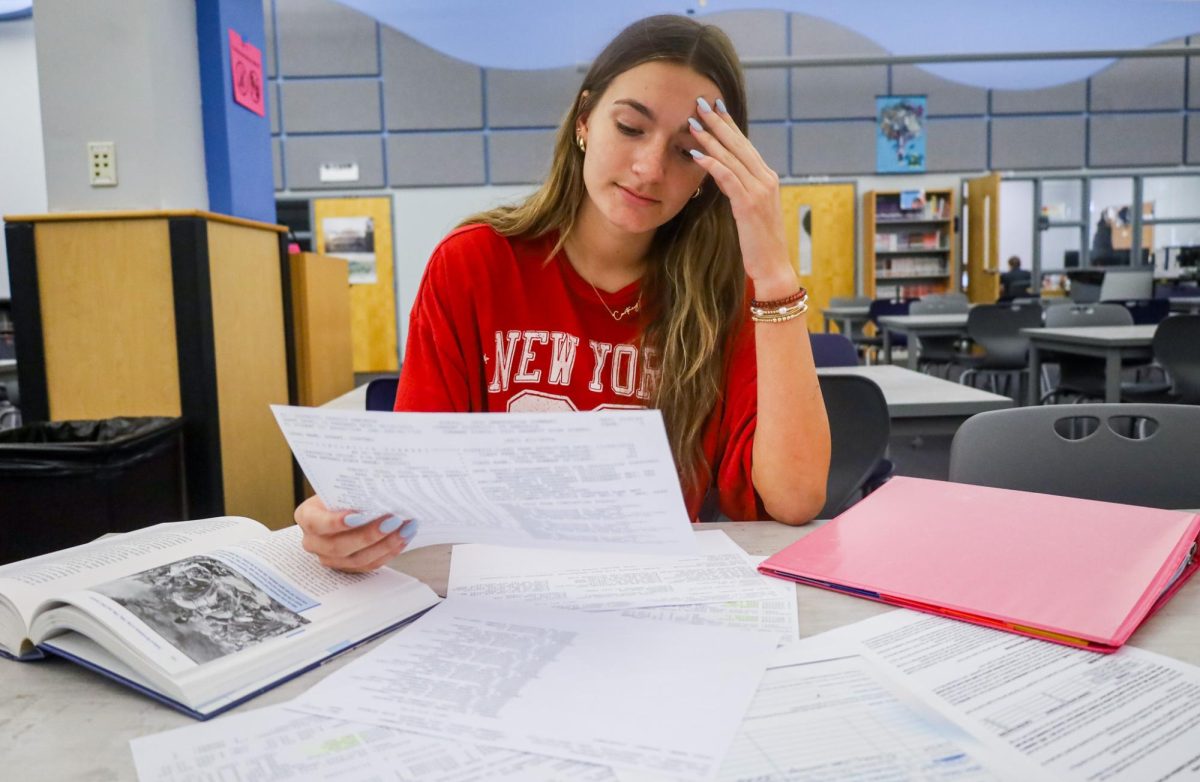

Students’ reading and analysis abilities have really felt the impact from the inflated sense of their skills caused by the lower standards for “advanced” classes. Comprehension of anything longer or more complex than a shallow anecdote has become a thing of the past.

And that’s to say nothing of writing. Every time an English teacher hands out an assignment, one question inevitably circulates: “Do we have to write in full sentences?” What have we become that writing a full line of text is too much to ask except in an AP class?

According to World Population Review, Florida has the third-lowest percentage of adults with basic literacy skills, with 19.7% of adults lacking basic reading and writing skills.

And a quick look at statistics from past assessments reveals that in 2024, only 60% of tenth graders and 61% of ninth graders in Seminole County passed the FAST exams—which basically only test the absolute minimum literacy skills required for a superficial understanding of texts. Nearly half of the SCPS population lacks reading comprehension skills at their grade level. You’ll never guess where these issues originate. (Hint: it’s the educational system.)

Additionally, kids end up wildly unprepared for AP classes and exams if they have only ever worked under the artificially lowered expectations of modern Honors classes. By collectively working to raise the standards for Honors courses, students, teachers, and administrators can ensure a more seamless transition from Honors to AP if students so choose to go that route.

Students need to self-assess and decide what environment will actually suit their needs and learning style—not what classes their parents think they should take. And schools need to re-normalize taking Standard classes as an acceptable alternative for students who need a higher degree of involvement from their teacher, so that Honors can serve as the middle ground between Standard and AP that it ought to be. Far too often, students think that they can handle a full course load of Honors classes, just because the notion of taking a Standard class seems so absurd.