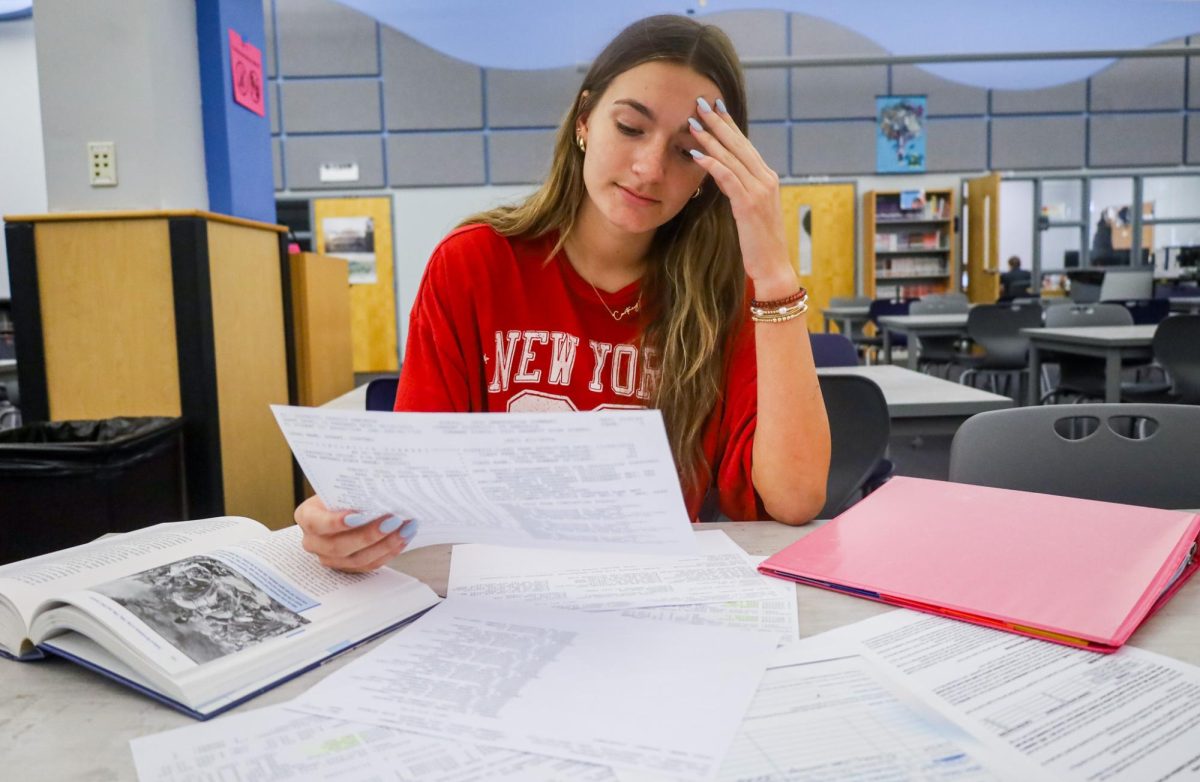

Senior Aleena Jacobs did not learn about the Soviet Union from her middle school World History class. She learned it from her mother.

“It was probably eighth grade where I learned about it in class and was like, oh, my mom’s from there,” Jacobs said. “I didn’t necessarily [feel] shocked or anything, but it was more like an acknowledgment of ‘Oh, my mom got out of there.’”

Jacobs’ mother, Svetlana, was born in 1976, the peak of the Soviet era. Amidst the nuclear arms race, rapid industrialization and class divides, Svetlana remembers a relatively peaceful childhood, growing up in a five-story apartment building with 100 other families.

“When you went outside, you could always find a playmate,” she said. “I remember myself from like five, six years old…once I was done with school homework, I would be spending hours and hours outside until bedtime.”

But even as a child, Svetlana noticed the government’s grip on citizens’ everyday lives.

“I lived during socialism, so school was free, medicine was free, [our] apartment was free,” she said. “But [voting], we had two choices…you could vote for or against. If in a specific geographical area there were too many votes against it, then the government would start looking at that area, maybe remove the mayor of that area…”

As a Socialist country, the Soviet Union was based on the idea of public, instead of private, ownership. On paper, the philosophy seemed utopian–a perfect society where everyone gets equal say in everything. However, in practice, it diminished people’s desire to work harder.

“You could be as good as you wanted or as bad as you wanted, you were still going to be paid the same amount of money and have the same lifestyle,” Svetlana said.

In addition, despite their “commitment” to equality, the Soviet Union was filled with class strife. Jacobs remembers an especially striking story from her mom, detailing how different classes had access to different foods.

“She told me that when you were in the USSR, based on your job, there were certain stores you could or couldn’t go to. My Baba and Deda weren’t able to go to certain stores..so when [my mom] moved to America, she [found out about and] loves condensed milk because she wasn’t able to have that in Russia,” Jacobs said.

Growing up, though, Svetlana never thought of herself as poor. She was just like all her neighbors, living with what they had.

“Money wasn’t such a focus back then, because nobody had enough money,” she said.

Within the borders of the USSR, Svetlana and other citizens were limited to government-approved broadcasts and newspapers, keeping them isolated from the rest of the world. Americans were portrayed as child exploiters, a myth that Svetlana looks back on with humor.

“We heard you [Americans] washed your driveways with some detergent…that was pretty weird [at the time] because we didn’t own a house. But now that I have a house, I get this service every so often, so I laugh at myself 30 years ago,” she said. “The newspapers would describe [Americans] like aliens that live somewhere on another planet.”

By the time the Soviet Union began falling in the 1990s, Svetlana remained relatively oblivious to American customs and habits. Even the color of American marketing was a shock to her.

“One feature of socialism is that since the government has everything, there are no brands. So you go to the store, you buy flour—it is a gray bag. It doesn’t say who made it. You go buy candies; again, they have different flavors but no brands,” Svetlana said. “When the borders opened, we started getting different products from other countries which were more colorful…a striking difference from what we were used to.”

After completing her bachelor’s degree in Russia, Svetlana moved to America for the master’s program at UCF. Education was not the only thing fueling her flight from the USSR—as the government’s power waned, crime rates increased, pushing Svetlana, with the support of her parents, to emigrate.

“Imagine the government has owned everything in the country, and then [all of a sudden] ownership needs to go to individual people. So how does it go to individual people? Either those in power grab things, or somebody who uses force grabs it,” she said.

Like any transition, Svetlana’s move to America was difficult at times. Although she grew up learning English, her skills were put to the test during daily conversations, and it took her a few years to really get situated. Throughout it all, Svetlana relied on a community of other Russian immigrants at UCF, bonded by their mutual understanding of each other.

“[I had] no family…international phone calls were $3 a minute back then or $6 an hour at that time, so there wasn’t much talking I could do,” Svetlana said. “Getting friends, talking to people who were here before me helped [a lot].”

In recent times, Russia has come under negative media spotlight, especially with their invasion of Ukraine in 2022. While Svetlana can not comment on her birth country’s stance on global affairs, she recognizes that the actions of the government do not accurately represent the feelings of the people.

“[Growing up] everybody wanted to be useful to society, to be a hero, to do something good, to help out neighbors, carry their grocery bags, walk the dogs, do things like that,” Svetlana said. “To me, one of the biggest bonuses of living here, having the citizenship of the US is I can go see the world, and I can have [all] these opportunities.”

Jacobs often sees her mother’s upbringing also play out in her objectivity to politics, a trait not commonly seen in today’s politically charged world.

“[Her opinions] are less conformed to specifically Democratic or Republic, liberal or conservative. They’re more like a blend between all the lines, instead of being confined to one specific political standing,” Jacobs said. “I definitely have some of her standpoints mixed in with me…my opinions also transcend lines.”

This year marks Svetlana’s 25th year living in the US. The days of Soviet Union power are far behind her, but her longing for her homeland is always close by. Every few years, Svetlana makes an effort to bring Jacobs back to Russia to keep her in touch with her roots.

“I like the fact that [Aleena] likes traveling [to Russia] with me so she can see what it is like now. I think most children, including Ali, feel that my childhood was centuries ago,” Svetlana said. “When we go back, I notice additional wrinkles in [my parents]…see the white birches, the national Russian tree…of course, it all makes me feel nostalgic.”

Despite being born in the US, Jacobs makes the effort to stay connected to her heritage. She eats Russian food weekly, and speaks mainly Russian at home. Like many children of immigrants, Jacobs has an intense curiosity of where she came from.

“I’m Russian, after all…I want to know the history of my country, what’s going on there, the traditions,” Jacobs said. “My mom doesn’t necessarily mention [her childhood] a whole lot, but when she does, it makes me realize that everything has its own flaws and its own good things.”