In third grade, senior Zahra Ateeq’s class held a world cultural day, one meant to celebrate the diversity of its students. Ateeq brought kheer, a Pakistani rice pudding dessert, to share with her friends.

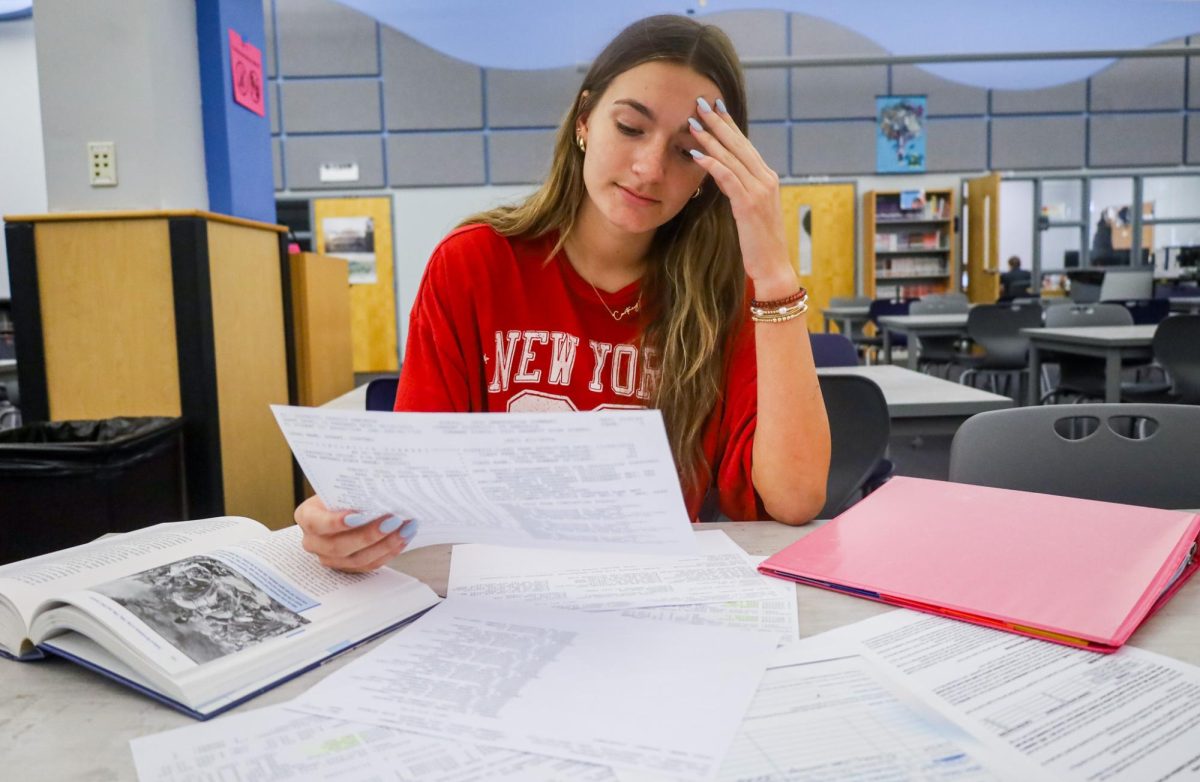

Her excitement quickly turned to dread as her classmates began spitting.

“[Everyone started] saying it was gross or that they did not like it. It was isolating…I didn’t want to be seen as odd and different, [so] I pretended that I didn’t like it either,” Ateeq said.

Ateeq’s experience is not unique. Food, a love language every culture shares, can be an easy target for people’s snap judgments, no matter what age they are.

Chinese teacher Zhenzhen Zhang moved to America after meeting her husband through a student exchange program. Despite mainstream Chinese dishes like orange chicken dominating the American palette, Zhang noted such acceptance does not extend to more niche tastes.

“Chicken feet, duck neck, stinky tofu…they’re so good, [but] people are always saying the food is gross,” Zhang said. “I just don’t take it to heart. They’ve never experienced it. They just have to learn a little bit more [about it].”

Despite the way food can be used to ostracize people, Ateeq has also found it as a connecting force. After years of growing up in a predominantly white school, Ateeq learned to spread her wings through her multicultural friend group.

“My friend group brings home-cooked meals to lunch…they definitely help me feel comfortable in my own skin and with bringing my own cultural food to school,” Ateeq said.

For senior Marlene Bekheit, one of Ateeq’s friends, food has always been a way for her to share her Egyptian culture and experiences. As president of the Coptic Youth Society, she hopes to encourage others to do the same.

“One of my favorite memories of the club was our Friendsgiving, where culture clubs like BSU, HSU and the Asian Culture Club joined together to share our foods with one another,” Bekheit said. “Food is more than just sustenance…it’s a symbol of my cultural identity that has been passed down through generations.”

Junior Ysabella Pierre-Louis agrees with Bekheit, especially since food is at the center of every social gathering in her household.

“I am Haitian American, and food makes up so much of my culture. We talk about food like we talk about weather,” Pierre-Louis said. “I always look forward to my grandma’s bonbon sirop (a sweet ginger bun) and akasan (cornmeal with cinnamon sticks).”

To junior Pablo Salinas, food has become especially important since he moved from Ecuador seven years ago. Despite the distance between him and the majority of his extended family, food always reminds him of home.

“We would always go to our grandma’s house on Fridays, and play a game called Treinta y Uno (31) [where] we’d bet with our grandmother with some cents she gave us. One time I got enough to go to the store around the corner and buy an empanada, which is a small thing, but it’s nice [to remember],” Salinas said. “Food just reminds me of where I’m from.”

On the other hand, Zhang also sees food as a reminder of the future. Ever since the birth of her son, Zhang has emphasized eating cultural food so her son can stay connected to his Chinese roots. To her, it is not only a matter of cultural pride, but survival.

“I didn’t think about [eating cultural food] before. But because of my son, I started prioritizing it more. I want to keep that part of our culture in my family for as long as I can, to make it as rich as it can be for my son,” Zhang said.

For Cyprus-born math teacher Aglaia Christodoulides, food is a record of her family history, capturing a melting pot of different backgrounds that make up her heritage. Growing up, her grandmother would always cook for the family, and she drew her inspiration from her Armenian neighbors.

“My grandmother was born and raised within the old city walls of the capital of Cyprus. There were a mixture of Greeks and Turks living together, so a lot of the food that she learned to cook was influenced by the Turks, so we grew up with the weirdest traditions,” Christodoulides said. “The Armenian style was amazing…my grandma [and her cooking] was the glue of the family.”

Sophomore Juliana Alvarez also gives credit to her grandmother for keeping her family traditions alive, not only through eating food, but making it too.

“Every year, my family and I gather to make bread or empanadas together. It became a family tradition, one special to me because my grandma would teach us how to make them,” Alvarez said. “With [every] dish, we get a taste of our culture and background.”

Although these cultures and backgrounds may not always be accepted, Pierre-Louis believes that intolerance has only drawn her closer to her Haitian family.

“At first, [of course] it was hard to hear someone call me ‘dirty’ and my food ‘disgusting.’ But as I got older, I began to embrace my culture more, to not be ashamed of the fact I was different. [In the end] it helped bring me closer to my culture,” Pierre-Louis said.