Sprinting across the field, varsity lacrosse midfielder Stacy Glover felt a pain shoot up her body. As a key player in the game against Vero Beach, she wanted to stay in the game, but she knew something was wrong and decided to come off the field.

“I definitely wanted to keep playing since it was a big game, but I knew if I did not stop I would be in even more pain,” Glover said. “I knew I would be hurting the team if I kept playing.”

Glover suffered an L5 and L6 fracture in her spine, from another player cross checking her in the back, that will never fully heal. However, Glover stretches and puts heat on her back regularly to combat the pain she is in. Glover was able to play again during her sophomore year as long as she used her therapeutic techniques.

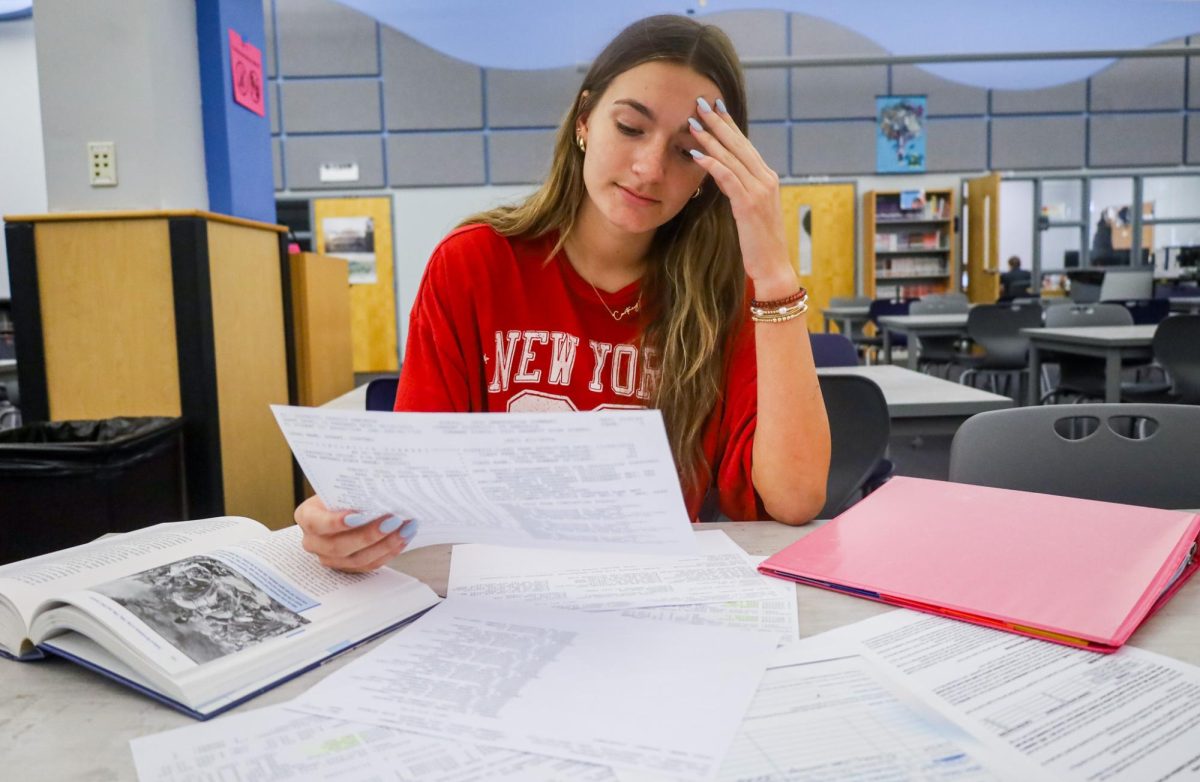

It took Glover months to speak up about her injury to her club lacrosse coach. When she finally did, she was met with disregard rather than concern..

“I felt pressured by my coach to keep playing even though it was only getting worse,” Glover said. “I was also scared to tell my parents because I did not know how they would react, they could have told me we need to go to a doctor or that I was just overreacting. It would have become real if I told them.”

Junior Jaycee Vanhoozer competes in the 169 lb weight class. During her sophomore year on the team she competed the entire season with a hip injury. After the season was over she learned she had to get surgery and has been recovering since then.

“There is a stigma about stopping in the middle of your season that I have heard, if you are strong enough to do your sport you should be strong enough to push through your injury,” Vanhoozer said.

Athletes tend to want to keep participating even though they are in pain because they do not want to let their team down. They feel a pressure that they put on themselves to keep going no matter what because their pain is temporary, even though it might not be.

“Most athletes want to continue going, even though the injury does not allow them to. The most frustrating part for us is when there’s a piece of bone that’s been damaged, they have to allow that healing to take place. Because if they do not, it will make it worse and potentially lead to surgery, which is what we try to avoid at all costs,” athletic trainer Keith Misseau said.

According to John Hopkins Medicine, about 30 million kids and teens in the United States play sports, and about 3.5 million of them get injured each year, meaning over 10 percent of student athletes get injured annually.

Miessau sees the majority of the student athletes who struggle with injuries like Glover’s, and a big part of his job is to rehabilitate students to make sure they can continue their athletic careers. Another important aspect is informing coaches, players and parents if an athlete cannot play any more.

“Parents don’t understand it. They don’t understand why their child just can’t play through it. I have had kids that would break their arm and get it casted, and parents do not understand why their kid cannot play with the cast,” Miessau said.

If a coach is either informed of an injury or suspects an injury, they are required to immediately inform the training staff to have the student-athlete checked out. The athletic trainer will then either clear or bench an athlete depending on their injury. If the injury is bad enough, they will refer the athlete to go to a doctor.

“The most important thing is to educate them. It is important to explain in the moment that it hurts not to play with your team, but it is about the athlete being able to function in the future and still play at the collegiate level,” Miessau said.

Education is not always enough, however. Some student athletes are scared to talk about their injuries to their peers or coaches because of a fear that they will be judged for having their injury.

“They might think you are faking it, just tired or overreacting. That’s why it can be scary to speak up sometimes,” Glover said.

When an athlete gets injured on the field, they have to make an immediate decision to either come off and treat the injury, or keep playing and possibly risk making the pain worse. Most will choose to stay on the field and keep playing. The line is hard to draw.

“Most athletes have a very high pain tolerance from the level we play at,” Vanhoozer said. “You know something is wrong when the pain is repetitive. Some things can fix themselves but if the pain never stops, that’s when you need to get help.”

It can be difficult for athletes to watch their teammates be able to play while they cannot, but Miesseau believes that they can still be a part of the team.

“They can still be a part of the team without participating, they can be a cheerleader from the sidelines and support any way they can,” Miesseau said. “It is important for athletes to remember that their injury is just a moment and not forever.”

Glover experienced being on the sidelines for a little over half a year and still came to every game and practice she could to support the team. Even though she has recovered now, Glover regrets not stopping sooner.

“I would have stopped playing earlier if I knew it would have made it worse in the long run,” Glover said. “I would do anything to go back and tell myself to stop playing because it just affected me for the worse.”