I have overheard many conversations in the hallways, quite a few of which have astounded me, but there is one I can never forget:

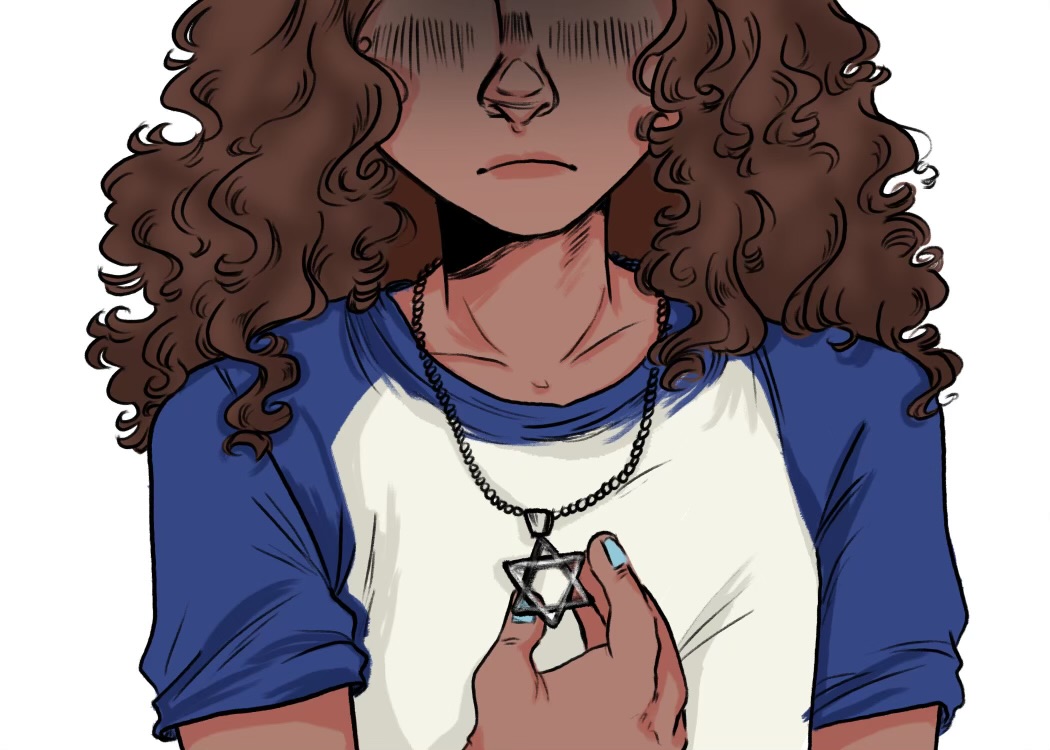

“Bro, did you see her?”

“Yeah, she didn’t say anything, but she’s totally Jewish.”

“Ew, definitely. She’s got that Jewish nose.”

I sincerely doubt that they would have said that if they had known that an ethnic Jew was walking behind them.

It was not their words exactly that bothered me—I had heard much worse before—but the raw hatred in their voices, and the way that they laughed so casually about it.

I am not particularly sensitive to rude comments, but at that moment, I was genuinely scared.

This is one instance out of thousands. Whether it is joking about the Holocaust in between classes, writing a threatening note, calling someone a “Jew” as a derogatory term or standing up in the middle of class and shouting “Hitler was right,” antisemitism has seen a troubling increase.

Though it is terrifying to watch it play out on a large scale in wars and mass shootings, it is sometimes even more threatening when it comes from the person next to you.

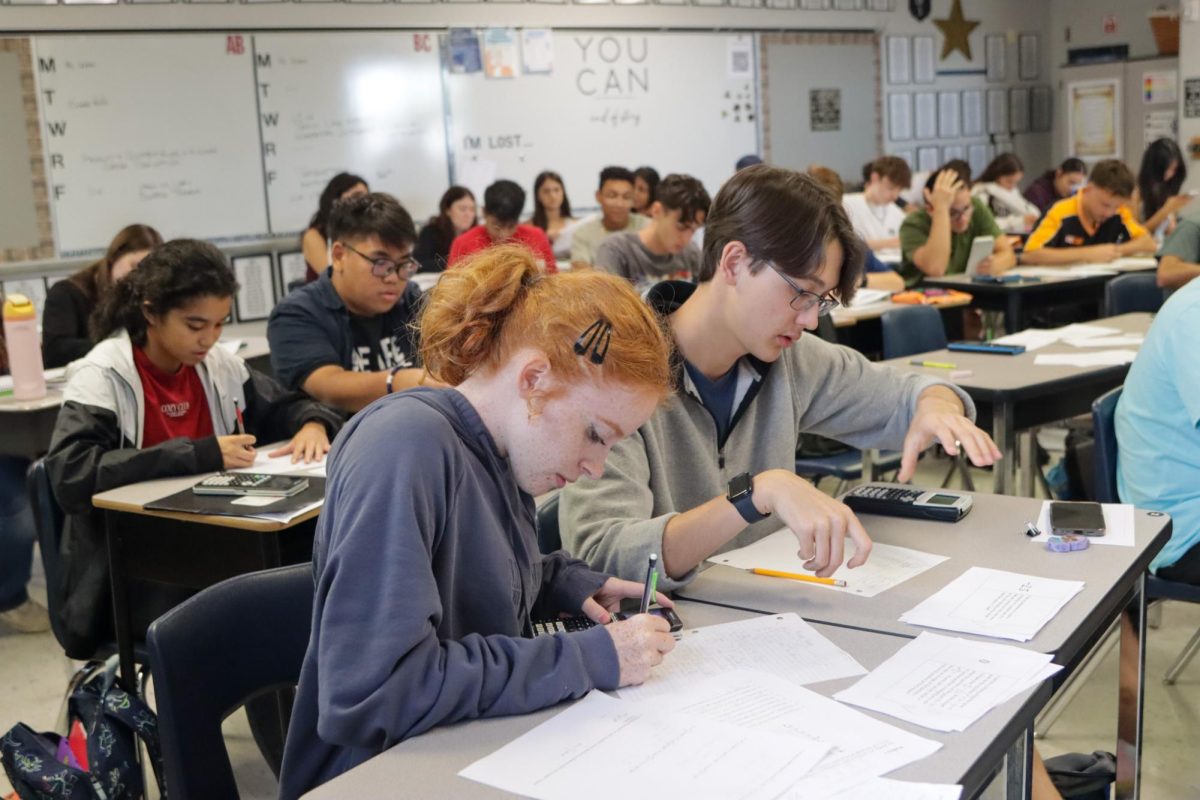

In an effort to bring more awareness to antisemitism and its historical impacts, social studies teacher Megan Thompson developed the school’s first ever Holocaust Studies class.

“The younger generations hear about [the Holocaust] and they have a kind of vague idea about it, but they don’t actually know about it,” Thompson said. “So it’s really important that we learn about it so that doesn’t happen again.”

One of the most important lessons that people need to learn is that the Holocaust is no joke. This topic should never be laughed about; any person who considers the murders and persecution of millions “funny” needs to reevaluate their definition of humor.

However, it is important to continue to educate students about it in order to prevent antisemitism that is fueled by ignorance. In schools, communities and society as a whole, the Holocaust needs to be talked about more and joked about less.

Part of the issue is the fact that people in majority-Christian areas, especially in the American South, tend to equate their religion with inherent goodness.

Phrases like “I’m a good Christian girl” and “that’s not a very Christian thing to do” are commonplace. And while not necessarily true, many consider going to church to be the ultimate symbol of moral superiority.

This causes people to fear anything that differs from the views of the majority—and that extends beyond just Judaism.

While sometimes overlooked, many Arabic and Muslim students have gone through similar experiences.

“They never say anything to my face, but I can hear whispers about stuff they’re saying,” Jane*, a Muslim student, said. “[I’ve heard] racist things about either Arabs or Muslims. Nobody ever comes up to me and says it, but you know because you can hear them saying that to their friends.”

The Israel–Palestine war has only escalated these tensions, giving rise to more anti-Muslim and antisemitic sentiments. It should be obvious that Muslim and Arabic students are not terrorists, just like not all Jewish students necessarily support all of Israel’s actions in occupying Palestine, but it seems that some people are still having difficulties separating the actions of a political or military group from the feelings of anyone with a cultural tie, no matter how weak.

In a place where the majority of the population is made up of Christian teenagers, this means jokes and comments about anyone who doesn’t wear a cross.

Certainly, there is nothing wrong with being proudly religious. In fact, the core messages of Christianity—and most other religions—emphasize respect, love and kindness, so it would greatly benefit society if people were to devote more of their effort to embodying and spreading those values, rather than preaching to those who do not follow their same religion. The antisemitic comments around school are doing anything but showing kindness.

People are inclined to label anyone who is different as “other,” and many subconsciously believe that being different is the same as being dangerous. This kind of fear and hatred is actually commonly seen in the earlier stages of genocide.

It seems like an exaggeration to claim that people in the United States are on their way to killing thousands of people due to religious differences, but wars have been fought over much less. Miniscule differences in theology—many of which modern-day Christians are not even aware of—caused the infamous Catholic-Protestant divide and a series of brutal wars all across Europe, and the way things are going, it is not uncommon for history to repeat itself.

Imagine what people will think of our current level of tolerance in 500 years. No wonder Jews and atheists are terrified.

This fear is not unfounded; antisemitic crimes have risen 37% in the past year, and in that time, violence and threats against Jewish people have been all over the news.

The extracurriculars list at Hagerty includes two popular, prominent Christian clubs, and no Jewish Student Union. This leads some Jewish students to feel as though they have little to no cultural support from the school.

When Christian organizations say prayers, they probably do not consider that a non-Christian might feel uncomfortable with it. Some sports teams even do a prayer circle before games or events, and many do not realize that it doesn’t feel great to someone of a different faith.

Sometimes it is okay to be lighthearted about a heavier topic, but there is a fine line between making something approachable and being offensive. Before making a comment about something potentially sensitive, though, stop for a moment and think. Would you say it to someone in the group that you are talking about? Would you be offended if someone said the same thing about your ethnicity or religion? When in doubt, keep it to yourself.

Some would say that this is oversensitive, and that little comments in the hallways do not really amount to much. However, it is these little bits of hatred that eventually become something much more significant. If students hear antisemitic or culturally offensive comments, or feel threatened by something that was said to them, they should not hesitate to report it to a teacher, guidance counselor, or administrator. It may seem like an overreaction in the moment, but perpetrators of hate crimes do not just pick up a gun one day without any forethought and decide to kill and injure dozens of people; at some point, they were that kid whose ignorance and bitterness was never corrected.

*name changed for privacy