Menstrual education is necessary, period

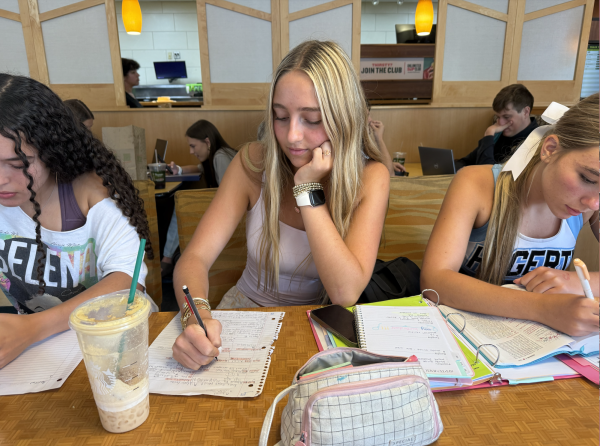

photo by Areli Smith

Girls across the U.S. get their periods, but those in Florida won’t be able to learn about them. On Feb. 22, HB 1069 was filed, restricting health and sexual education for those under sixth grade, including period education.

The jog in from recess leaves many girls covered in sweat, dirt and grass stains from their outdoor play. Walking into the bathroom, one girl discovers a concerning spot on her shorts—one that doesn’t look like it came from a game of tag. Unsure of what to do, she goes up to her teacher to ask for help, jacket tied around her waist with embarrassment.

The teacher would help, but a new Florida law prevents her from saying anything other than, “You better call your mother,” leaving her student in confusion, discomfort and worry for the rest of the school day.

This is the future the Florida House has begun to carve out for young girls across the state with House Bill 1069.

HB 1069 was first filed on Feb. 22, but has quickly gained national attention for its potential restrictions on sexual education. Aside from attempts to encourage and teach the “benefits of monogamous heterosexual marriage,” this bill restricts sexual education to only grades six and above. Due to the bill’s poor wording and open-ended interpretation, many now fear that this will also ban schools from teaching about the menstrual cycle, or periods, to younger students. While Florida Rep. Stan McClain stated this was not the intention of the bill, he confirmed at a House Education Quality Subcommittee meeting on March 15 that this bill would ban students from having any questions on menstruation answered at school. The bill states that all instruction on material relating to “acquired immune deficiency syndrome, sexually transmitted diseases, or health education” will be included in the ban. While it might make sense to push back instruction on AIDs or other STDs, a pivotal and daunting point in young girls’ lives could now be met with indifference and little concern from their teachers and lawmakers.

How can a topic be categorized as “not appropriate for the grade and age” of a student if one’s body has already begun this development? Waiting to educate students about menstruation until they enter middle school is like telling a pregnant woman to use contraceptives—it is too late.

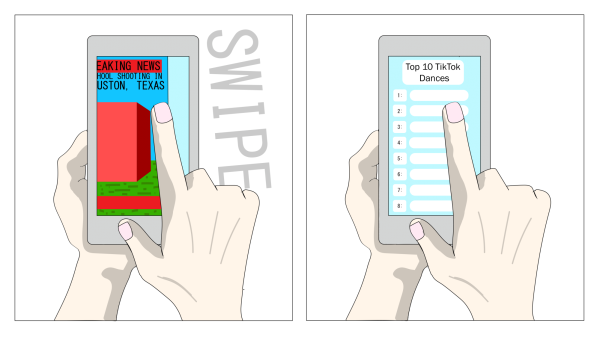

Why should a child not be given the right to learn and understand what is happening within their own body? It seems to be a recent trend in the U.S. for a majorly male law-making system to restrict women from education and resources that pertain to health struggles only they can experience or relate to. The federal government believes women shouldn’t be able to have control over their own pregnancies, but also refuses to give them proper sexual education from a young age? It doesn’t make sense.

Why is a completely natural and normal step of female puberty becoming sexualized and deemed as not fit for the school environment? This can be attributed to the long history of the sexualization of young girls, whether it be intentional or not. Common changes such as getting their first period, beginning to develop breasts or constant reminders to cover their shoulders instill a belief in young girls that their bodies are inappropriate and should not be spoken about—gross.

By placing menstrual and health education in a connotation of being sexually explicit or unbecoming, the Florida House further encourages the idea that periods are not a topic to be discussed—an idea that puts many young students in danger.

When a student throws up, their teacher cleans them up and brings them to the nurse. When a student has a runny nose, their teacher provides them with tissues. When a kid gets hurt on the playground, their teacher wipes away their blood and brings them to the nurse for a band-aid.

These are all completely natural and common situations that happen in the classroom. But why are teachers allowed to hand out tissues and not pads? The answer—periods are being seen as a mature subject matter, despite their biological and normal nature. The gender bias placed against women starts at an early age, and this is just another example of U.S. lawmakers telling young girls that their bodies, their changes and their struggles don’t matter—which isn’t anything new.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, menstruation can begin as early as age 9 or as late as age 15, with the current average age in America being age 12. However, this statistic is steadily declining and concerning when compared to the average recorded in the last century of 14-years-of-age, according to the Center for Disease Control. As much as six months earlier than recorded in the last 20 to 30 years, the age of menstruation in America is only getting younger, making this bill even more threatening.

Under the American public school system, nine-year-olds are typically between the grades of third and fourth, placing them below the proposed sexual health education bracket. However, according to Scientific American, it is not age that triggers menstruation, but estrogen levels. The most common sign of female puberty that can trigger this spike is breast development, further sped up by one’s body mass index or BMI. According to the CDC, the average American girl’s BMI has increased from 15.8 to 16.6 in the last 40 years and the average teen’s has increased from 21.9 to 24 over the same period.

In summary—children are bigger than they were 40 years ago.

This discovery explains that the age of menstruation is continuing to drop in America as BMI rises, an issue not new to our nation. So rather than being a development triggered by age or maturity level, puberty can be directly associated with weight.

So, would the Florida House ever change the ban from fifth grade and under to 100 pounds and under? Besides the fact this is an outlandish idea, adult male lawmakers in Florida likely do not understand the science behind female puberty, making it near impossible for them to create a biologically accurate law.

If students are not educated from a young age on how to care for themselves during their period, serious health and safety concerns may arise. Proper period care involves an understanding of how to keep the area clean, correct usage and disposal of menstrual products. Serious medical emergencies such as toxic shock syndrome, a life-threatening bacterial infection, can result from keeping products like tampons or menstrual cups in for over the recommended time. While many young girls do not use these products when they first begin their cycles, it is still important to understand what risks could arise in the future if proper care and precaution are not taken.

In addition to the bill’s restrictions on this vital health education, period products have and will continue not to be provided in schools. Despite efforts from global organizations such as Period.org and local groups like Hagerty’s Girl Up Club to fight against period poverty—a lack of access to menstrual products—500 million people lack access to menstrual products in the U.S.

Instead of banning education, the Florida House needs to provide its people with the proper tools to take care of their bodies. Rather than making an already difficult transition for young girls harder, teachers should be able to guide their students when in need. No girl wakes up one morning and decides “I’m ready to get my period.” No girl enjoys getting her period or “reaching maturity” at a young age. No girl will have the same experience getting her first period as another. Periods are a different and unique experience for each girl—one that can’t be restricted by law or determined by grade. So stop making periods out to be an adult subject matter when it is truly a matter of health.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Hagerty High School. We are an ad-free publication, and your contribution helps us publish six issues of the BluePrint and cover our annual website hosting costs. Thank you so much!