Your donation will support the student journalists of Hagerty High School. We are an ad-free publication, and your contribution helps us publish six issues of the BluePrint and cover our annual website hosting costs. Thank you so much!

Where are all the girls?

The push for more girls in STEM is evident, but big gender gaps still exist in the classroom.

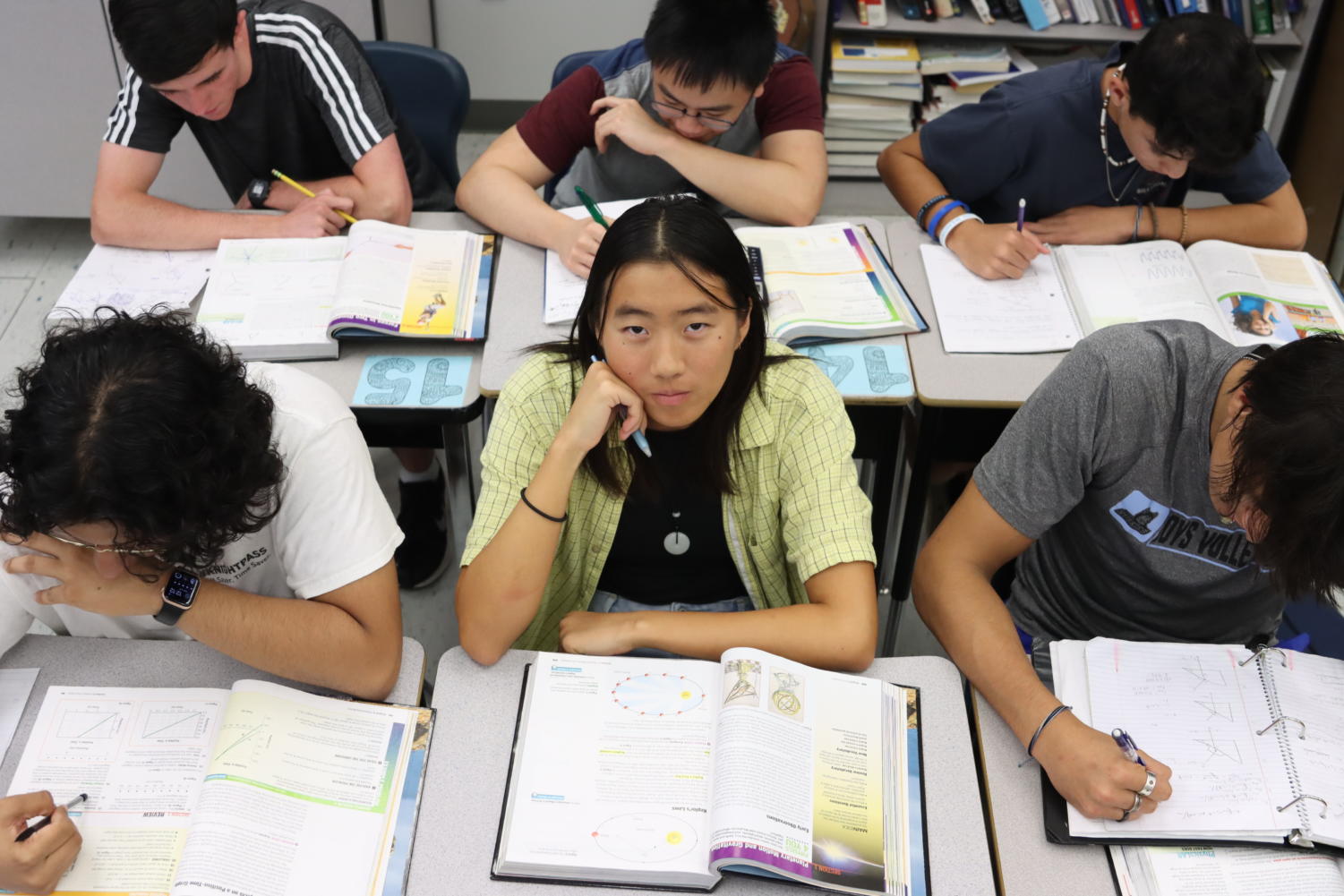

When senior Helen Zou walked into her second period AP Physics C class, she took a look around. Tristan. Rylan. Connor. Xander. Although slightly disappointed, Zou was not surprised. What started as 15 girls matching the 15 boys in her freshman science class dwindled down to 10 girls in her sophomore year, then six in her junior year. Now a senior, Zou is the only girl in her class of five, a phenomenon that is not unique at Hagerty.

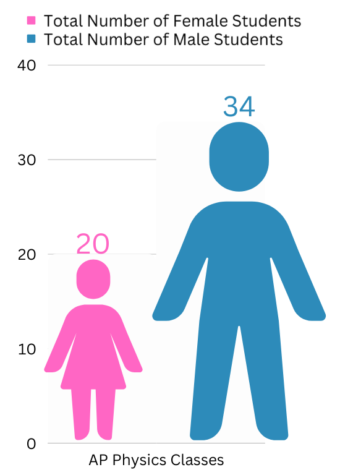

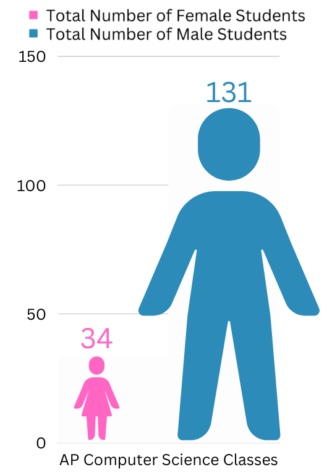

With a projected growth rate of 10.5% between 2020 and 2030, STEM occupations are the fastest growing field for high school students. However, despite the opportunities that come with a STEM career, few girls are choosing to pursue one. Nationally, women in college made up just 19% of computer science and engineering classes in 2017-2018, with a slightly higher percentage (39%) taking physical science classes. On campus, girls make up just 21% of all computer science classes, with a slightly higher percentage (37%) taking AP Physics classes.

“[The gender gap] is a bit strange, but I wanted to challenge myself because I want to pursue STEM in the future,” Zou said.

Traditionally, the AP Physics C class has always been a small one, with two girls in a class of 12 last year. AP Physics C teacher Darlene DePalma notes that the number of girls enrolled has been decreasing in recent years, along with overall enrollment.

“I think boys are pushed more than girls [into STEM],” DePalma said. “Girls just grow up hearing, ‘You’re not good at math, you’re not good at the physical sciences.’”

Senior Bernice Wong, who has a 4.519 GPA, took AP Physics I but chose not to go onto AP Physics C, attributing her decision to her worry that she would not understand the content and that she would feel isolated as the only girl.

“I didn’t want to take [AP Physics C] because I didn’t want to do badly in it,” Wong said. “And if I’m one of the only girls in [the class], I don’t want to be seen as the ‘dumb girl.’ I wasn’t that good at AP Physics I, so I chose not to take AP Physics C.”

Although Wong chose not to take AP Physics C, she did take AP Computer Science A, since she wants to pursue computer science in the future. In her class of 40, just 11 are girls, while in the AP Computer Science Principles classes overall, only 18%, 23 out of 125, are girls. Junior Abigail Heimendinger, who also takes AP Computer Science A, thinks girls might not choose to take the course because of their desire to take the same classes as their friends.

“[Computer science] is a male-dominated field,” Heimendinger said. “There’s not a lot of girls in the class already, so if you’re a girl, you don’t want to be surrounded by a bunch of guys. And I think not a lot of girls continue because a lot of their friends aren’t taking it.”

Although the effects are only being seen now, the causes of the STEM gender disparity are rooted in the past, back in the halls of preschool and kindergarten.

“Honestly, I think a lot of it starts at home,” DePalma said. “It’s the way girls are raised at home compared to boys. Boys get all the hands-on toys and building stuff and girls get the dolls and the vacuum cleaners.”

Growing up, robotics sponsor Po Dickison had a similar experience. Despite her love for math as a teen, Dickison said because nobody encouraged her to pursue that passion, it eventually died out.

“I loved math and science growing up. I wanted to be a pharmacist,” Dickison said. “But I didn’t have anybody who encouraged me. So I ended up pretending I hated it, and I just stopped taking [STEM] classes.”

Years later, Dickison began to reflect on the missed opportunities she had as a child. Merging her passion for teaching and her reignited love for STEM, Dickison became the robotics sponsor.

“I thought, I wish I had somebody who encouraged me back in high school,” Dickison said. “So maybe if I spark an interest in one or two kids, then hey, I’m making a difference.”

Today, Dickison marks her 13th year as a robotics mentor. What started as a small program with one team has grown to encompass five teams and 46 students, with many qualifying for international competitions.

“If I could go back in time, I’d say to young Po, ‘Stick with it,’” Dickison said. “And I always try to tell girls, just because they’re boys doesn’t mean they know everything. Don’t give up. Don’t let that intimidate you because then it might be a missed opportunity. So I really try to stay positive and to encourage everyone, especially girls, don’t be afraid and show up.”

The problem is not just at Hagerty. According to UNICEF, girls have lower self-confidence in their STEM abilities than boys in most countries, even though they scored the same or higher than boys on tests. This lower self-confidence leads to lower interest and enjoyment in STEM, and subsequently fewer girls pursuing STEM careers.

Even so, the few who choose to do so are often at the top of their class. While Zou is the only girl in her AP Physics C class, DePalma notes that she easily competes with the rest of the boys.

“She’s a great student,” DePalma said. “Sometimes the boys will group up together but her grades are right up there with the boys. The girls that come into this class are well above the boys. As far as math intellect goes, that’s what I’ve seen every year.”

Physics teacher Amany Bekheit saw this same trend in her classes. After seeing that she only had one girl in her fourth period class last year, Bekheit put together a survey to find out why not many girls choose to take AP Physics.

“I hope a lot of girls take the survey because what I noticed in UCF and in the workplace is that they’re trying to recruit more girls to be engineers, scientists,” Bekheit said. “So why not try that career and take [AP Physics], because it’s going to open so many doors.”

Although a gender gap can be seen in STEM courses, some girls are using clubs and extracurriculars as ways to encourage girls to join STEM. Senior Grace Catina, president of Science Olympiad, says she always tries to advertise the club to more girls.

“I tell them that there’s a lot of girls that come [to the club] and there’s a lot of girls that compete from other schools,” Catina said. “And obviously, I’m a girl so I’ll always be there to help them out, but it’s not as overwhelming as you think. If anything, the girls do really well when they work together in an event because they just have that strategic mindset.”

Catina, who decided to pursue biomedical science after attending a science camp in fifth grade, believes the presence of just one girl in a room full of boys can inspire other girls to follow.

“Girls in STEM encourage other girls,” Catina said. “When I’m in Physics class, I have a lab group and there are a couple girls in the class that band together. So it’s really encouraging to have other girls that are in the same place to talk to.”

Science Olympiad Vice President Mohanashree Pamidimukkala agrees, noting that simply seeing girls participate in robotics competitions motivated her to keep pursuing STEM.

“At my old school, there were certain robotics teams that were all girls,” Pamidimukkala said, “and those were just really inspirational to see a bunch of girls come together and have a passion for STEM.”

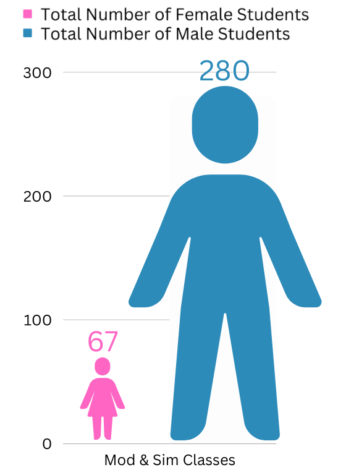

As vice president of Mod Squad, senior Emma Lundquist hopes their advertising and outreach will encourage more girls to join the school’s program of emphasis, Modeling and Simulation, in the future. In her last year of Mod and Sim, Lundquist still remembers walking into her freshman class and realizing she was one of the only girls in the class. Across the Mod and Sim program, girls make up just 19% of students. Lundquist says that although the initial realization that she was one of the only girls in her class was shocking, it only motivated her to continue pursuing STEM.

“I mean, you look around and you go, ‘Wow, there’s no girls.’ There’s nobody else and it feels a little lonely, but it also gives me more determination to stay in the program,” Lundquist said. “It’s not going to be anybody else, so why can’t it be you?”