Accommodating the narrative

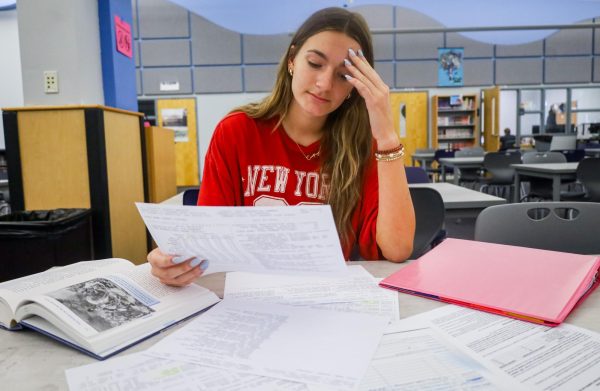

photo by Dylan Wisner

IEPs and 504s are intended to uplift students that struggle with disabilities. “[Without an IEP] I’d have problems with things like taking tests, and I don’t think I’d be able to have a safe space,” John said.

Trying to educate 2,356 different students the same way is like trying to paint a rainbow with only one color. Whether a student is eligible for the Exceptional Student Education program, an Individualized Education Plan(IEP) or a 504, accommodations help level the educational playing field.

“I realized I needed [an IEP] when I started high school. I couldn’t just breeze by anymore, and I actually had to try to be at the same level as my peers,” junior Nina Honda said.

An IEP is an education plan tailored to a specific student’s needs. Depending on the disabilities they have, counselors, parents and support facilitators work together to assign specific classes that would best fit the student. Honda only recently became eligible for an IEP, but being previously diagnosed with ADHD, was already familiar with how the disorder could impact her education.

“Instead of being hyperactive all the time, I have an inattentive type, which looks more like being distracted all the time,” Honda said. “I would forget to turn in assignments that I completed, I wouldn’t pay attention to what the teacher is teaching in class, and I would get distracted while taking tests or quizzes. Now that I take medicine and have developed coping techniques, I do these things less frequently.”

Developing and implementing an IEP depends on communication between counselors, students, parents and medical professionals, according to IEP counselor Erin Isaacs.

“I help facilitate between the teachers, support facilitators, the students and parents,” IEP counselor Erin Isaacs said. “If we get a new student with an IEP, I’ll read it to determine the classes that they need.”

Qualifying for an IEP requires a student to have a certain impediment that affects them in class. In order to determine if an IEP is suitable, the program takes grades, test scores and classroom conditions into account, but in Honda’s case, grades alone were not what granted her an IEP. Although her scores were not much different from an average student’s, Honda knew that an IEP would save her from struggling without accommodations, which entailed hours of re-reading material and re-learning lessons.

“A lot of students don’t just fail their classes, they’ll try a lot harder than their peers,” Honda said. “I get distracted during class, and the teacher will call on me, and I have no idea what’s going on. Or I’ll just completely spaced out during the entire class, and then I just don’t learn any of the material.”

According to Seminole County’s “A Parent’s Introduction to Exceptional Student Education,” those assigned to a student’s IEP follow the Multi-Tiered System of Supports process by using past medical records, school progress reports and evaluation reports to decide if a student needs ESE services.

“Talk to the current counselor that you have, and they’ll be able to look at the process and get that ball rolling,” Isaacs said. “We look at the entire picture to determine if a student is eligible.”

For John*, ESE services became an integral part of his education in sixth grade, and he has since grown accustomed to what it means and how he can use it to best facilitate his education.

“[In sixth grade] they added extra time and help in specific classes, and in ninth and tenth grade, they started to repeal some things because I started getting used to school in general,” John said. “At any point in time, you can go to someone and amend your IEP.”

Amending an IEP might be a convenient process, but John struggles with its other aspects, such as its classroom dynamic. In his Social-Personal class, one assigned specifically within IEPs, students with widely varying needs often get put into the same classroom, and the environment can grow disruptive.

“For a person who has an IEP, I basically end up stressed at every period of the day,” John said. “And as soon as I walk out, it feels better. But then I have to deal with that stress all over again. It’s just compounded stress.”

IEPs and 504s are seldom looped into the same category, as they each adjust a student’s learning environment in completely different ways.

“A 504 is for students with disabilities that need accommodations. This is not a specially designed instruction,” Isaacs said. “It’s designed to let students have an even playing field within the classroom.”

504s provide accommodations without affecting students’ curriculum. Both can grant adjustments like extended time or preferred seating, but 504s cover a broader range of disabilities, both temporary and permanent.

“They knew that I had ADHD since I was really young, and mine was pretty severe,” senior Allyson Myers said. “They got me a 504 when I first went onto medicine, because I was a really troublesome kid, to the point where I would do nothing but peel the papers off of crayons.”

Myers has had a 504 since first grade. Originally, it only entailed access to extended time or written notes, but she was later diagnosed with Dyscalculia during her junior year, a learning difficulty that prevents her from remembering basic arithmetic, which warranted the addition of a calculator accommodation within the classroom and on standardized College Board exams.

“Accommodations for school-based exams are in place with IEPs and 504s,” Isaacs said, “But any accommodations for the ACT and College Board exams have to be applied for and are not guaranteed.”

Because school counselors have no jurisdiction over College Board exam conditions, Myers struggled to get any accommodations regarding Discalculuia on certain tests, and the process required constant communication through her counselor, a psychiatrist and rejections emails.

“When I tried to petition for the [accomodation], given that I have always had a calculator accommodation at the school, my request was rejected,” Myers said. “So we had to file an appeal, but the appeal got rejected, so I had to take a full psychiatric evaluation, get a full diagnosis, and an official recommendation from the psychologist.”

The process might have been tedious, but Myers deems it necessary to maintain legitimacy among accommodation requests.

“The fact that [students] are able to take advantage of accommodations that people actually, genuinely need is minimizing,” Myers said. “I am now afraid that I am taking advantage of the system for getting accommodations that I actually need. I have a mental disability and I feel like I am doing something wrong because that is the trend that has been set.”

Exploited accommodations are just the tip of the iceberg as Myers is also forced to face misconceptions about her disability, her intelligence and her own validity as a 504 student on a regular basis.

“I am both a gifted kid and a kid with accommodations, so I’m known as twice-exceptional, and that is the hardest thing to be in the system,” Myers said. “It is hard for people to understand that just because I understand things quickly does not mean that I can’t have a learning disability, and it becomes an even harder fight for someone with such a high SAT score to say ‘I genuinely just don’t understand.’’’

Many students with accommodations, whether it be an IEP or a 504 plan, struggle with miscommunication with their teachers on how they should operate in the classroom, but Isaacs ensures that in every situation, a counselor or support facilitator should always advocate for students’ needs.

“We need to be made aware if a teacher is not implementing something because there are so many check and balance systems for that,” Isaacs said. “If there’s ever a concern, talk directly with a teacher, and if it’s not resolved, go directly to the counselor, who will help facilitate the process.”

Despite suffering an ineffective adaptation at the hands of College Board, accommodations continue to uplift students with disabilities within their respective schools.

“I have had teachers that were supportive,” Myers said. “One teacher gave me a paper at the beginning of the year that asked if I wanted her to assist our accommodations or if I was comfortable with her talking about it, and she always made sure our accommodations were taken care of.”

*name changed for privacy

Your donation will support the student journalists of Hagerty High School. We are an ad-free publication, and your contribution helps us publish six issues of the BluePrint and cover our annual website hosting costs. Thank you so much!

![IEPs and 504s are intended to uplift students that struggle with disabilities. "[Without an IEP] I'd have problems with things like taking tests, and I don't think I'd be able to have a safe space," John said.](https://hhsblueprint.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Image-900x900.jpeg)